Century of Endeavour

The Co-operative Movement in the 1910s

(c) Roy Johnston 2003

(comments to rjtechne@iol.ieThere is a reference in the TCD Board Minutes dated October 18 1913 to the foundation of a consumer co-op to supply groceries to the students, and JJ had a hand in this; he appears explicitly later on, in the Board minutes, in this context.

According the the minute-book, which is available in the MS room of the TCD Library, the first meeting took place on August 25, with Rudmose-Brown in the chair, and WJ Bryan as secretary. The committee included JW Biggar, R Hannay and RN Somerville. The manager was SE Murtagh at £2 per week, and there was £318 share capital.

The first meeting with JJ present took place on Tuesday November 11 1913; at this they planned the first general meeting which took place the following Friday, November 14, in the Graduates Memorial Building; this is the relatively prestigious location where the Hist and the Phil meetings take place, suitable to the status of the event: Provost Traill had agreed to be the President, and there was an Honorary Council which included Sir Horace Plunkett, Father Finlay, Sir Henry Bellew, George Russell, Harold Barbour, and one 'Captain Bryan' (this was WJ Bryan's father, an establishment figure.) The working committee included Professor Bastable, Joe Biggar, EW Deale, WJ Bryan and JJ, who was in a position to parade his recently-acquired status as FTCD.

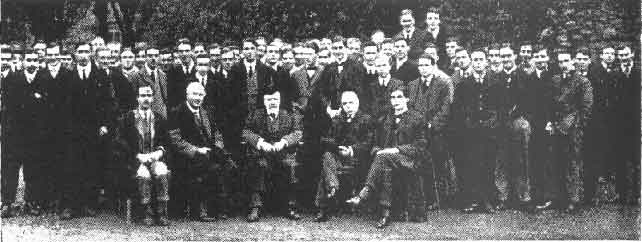

This photo of the DU Co-op Society foundation group was published in the souvenir book issued to the participants in the 1914 Dublin congress of the Manchester-based Co-operative Union. Provost Traill is seated, central. JJ is standing, front row, left.

The foregoing was the committee's plan for the inaugural general meeting, which took place, chaired by Rudmose-Brown; Joe Biggar was Secretary. There were 18 people present. The committee agreed to meet monthly on the first Monday at 3.15 pm. Delegates were appointed to attend the 64th Southern District Co-operative Conference on November 22: Miss Renton and the Secretary. On December 1 they met again, with 10 people present, and agreed to subscribe one guinea to the Co-operative Congress; presumably the delegates reported back positively.

They met again on January 26 1914; there were 14 people present, including JJ; it was agreed that Sealy Bryan and Walker should print the annual accounts. (This firm of jobbing printers were, it seems, occasional publishers; their imprint is on JJ's 'Civil War in Ulster', which they had published the previous October. I suspect that JJ got them the co-op business, such as it was, as a friendly 'thank you' gesture.) At the February 23 meeting, in JJ's absence, with 17 people present, Joe Biggar proposed JJ as Secretary and he was elected, and appointed to attend the general meeting of the IAWS. Suppliers cheques for some £160 were passed.

The 46th Annual Co-operative Congress was held in Dublin, on the Whit weekend, 1914. The Handbook of this conference contains a review of the consumer co-op scene in Ireland, which was quite undeveloped; it would have been matched by one of the smaller English counties. The Congress was held in Dublin as a gesture in the direction of strengthening the Irish district, and mending fences with the IAOS, with which they had been in dispute in the 1890s. The Co-operative Wholesale Society had attempted to establish creameries in Ireland, but these had mostly failed, being superseded by the IAOS creameries, which depended on local societies appointing their own managers. The emerging Irish movement had found the Co-operative Union structures too inflexible.

The embryonic Dublin consumer co-ops however remained with the Union; they existed in Rathmines, Inchicore, Thomas St, Dorset St and Fairview. The Inchicore one went back to 1859, and serviced the railway workshop workers; it was criticised in the Handbook for being exclusive.

The Dublin meeting of the Union in 1914 was thus a false dawn; it seemed to open for JJ a window into Irish co-operative politics, for which he then had hopes, but these proved illusory.

JJ would by then have applied for the Albert Kahn Fellowship, but I suspect that he regarded it as a 'long shot', and did not expect to get it, or he would not have taken on the responsibility of being the DU Co-operative Society Secretary. Meetings then become quarterly; there was one on May 4 1914; the minutes are in JJ's writing; there were 11 present; discount deals for students with firms were announced. The Secretary JJ was sent as delegate to the forthcoming co-operative conference.

JJ attended this, which took place before he left on his Travelling Fellowship. There was a Congress group photograph, which I recollect having seen, years ago; this with luck will turn up when I get a chance to go through the attic (in the end it has surfaced via the Plunkett House library). All this confirms my earlier impression that the politics of the Irish co-operative movement was top of JJ's priority at this time, remaining so for more than a decade, despite the diversions of the national revolutionary period. He did however in the 1920s turn his attention to the IAOS and Plunkett House, once it became apparent that the Co-operative Union was not a viable prospect in the Irish context as it had developed.

There was an emergency meeting of the DU Co-op Society on May 28, with references to price and quality problems, 'prehistoric butter' etc; it was agreed to display a price-list, and to put a notice in the Calendar advertising the existence of the co-op as a service to students living in. This however did not appear. The next meeting was on August 19; the war had broken out, and JJ was in the throes of his first abortive attempt to get started on his Albert Kahn Travelling Fellowship. Various acting secretaries took the minutes in his absence, and the business fell into some disarray; the agenda includes issues like the fate of the Society's cat. Meetings in the first half of 1915 were poorly attended (9, 7, 5, 9); decisions about affiliation were postponed; arrangements were made for a temporary job for the Manager during the long vacation.

Then at the November 22 meeting, JJ came back, and took over doing the minutes; he wrote marginal notes on the earlier minutes, realising the extent to which things had fallen apart in his absence. The agreed to take some trial copies of the Irish Homestead. Then at the December 3 meeting, with 10 present, JJ's detailed minutes include a decision to try to capture the trade of the College Kitchen for the IAWS, with some aggressive marketing. This came up at the Board, and the latter agreed to leave it to the Bursar's discretion, a rebuff. The decision to cultivate relations with the IAWS, which was related to the IAOS rather than to the Co-operative Union, was an indicator of a turn towards Plunkett House.

At the meetings in the first months of 1916, with JJ as secretary, there was evidence of a major effort to get more business; there was an attempt made to do a deal with the Dublin Consumer Co-op secretary to encourage non-College Dubliners to shop in the College, making postal or phone arrangement; this looked somewhat like grasping at straws. Business was in decline because of the decimation of the College population due to the war. Then came the Easter Rising, and the shop was occupied by the Officers Training Corps, which was defending the College against the insurgents. JJ as secretary was reduced to writing letters to the military HQ looking for compensation, which by the end of the year they received. JJ's last 1916 minutes were of the meeting on October 16. He continued to attend the meetings, with the status of Secretary.

At a meeting on December 14 1916 it was decided unanimously to record a vote of sympathy with Lt-Col Bryan, (the 'Captain Bryan' earlier mentioned as being on the Honorary Council) on the death at the front of his son WJ Bryan, founder of the Co-op. Lt-Col Bryan had written to JJ on 12/12/16 from his home in Norwich, to thank him for his letter of sympathy, and in turn he wished to thank TCD for 'saving the family plate during the rebellion, it was in the Bank of Ireland'(!).

During 1917 JJ's younger sister Anne was in College, and she attended meetings, alternating with JJ, who was otherwise engaged, working on a committee with James Douglas, George Russell and others producing documentation for the Irish Convention. The co-op had slipped down somewhat in his list of priorities, but the minutes are mostly in his hand. The Bursar was continuing to deal for the College Kitchen with the firm of Andrews, and, according to a letter from HMO White, would use a co-op tender document to beat Andrews down, rather than to take it up. Hostility to co-operative retailing was, it seems, deeply ingrained in the culture.

There were insights into co-operative politics: at a meeting on May 7 1917 the question came up of whom to vote for as the Irish representatives on the Board of the Co-operative Union (an all-UK body). It was agreed to vote for Smith-Gordon, Tweedy, Palmer, Adams and Fleming. Smith-Gordon had been encountered by JJ in Oxford, where he had shone as a socialist debater in the Union. RN Tweedy was an engineer who subsequently became a founder member of the Irish Communist Party. The co-operative movement in this period was a focus for those who wanted to democratise the economic system from the bottom up, and who identified with the politics of the Left in this spirit. At a subsequent meeting on February 26 1918 RN Tweedy was nominated to the Board of the Irish Section of the Co-operative Union.

There began to be echoes of the national struggle: on May 21 1918 JJ as secretary was absent; it was reported from the Chair that he had been detained at Baldoyle by the District inspector of Police. Then on December 1 Rudmose-Brown resigned as Chairman, in a friendly letter to JJ, pleading pressure of work. He was replaced by (Gerry?) Oulton. In December they set up a 'propaganda committee' to canvass non-members living in college, and to investigate causes of complaint.

In 1919 business began to take up again, with students war-survivors trickling back. Roles of committee members were defined: there was a sub-committee to keep in touch with the needs of the junior years. Then at the end of 1919 they pulled off the deal that set them up viable for the long haul: they set up the Lunch Buffet, in the Dining Hall. This was an immediate success, and gave a good foundation to the wholesale purchasing operation, which they did via the IAWS. JJ then took over the Chair, which he occupied up to the end of 1922. He pulled out of active participation on co-op affairs once he saw it was on a sound business footing.

JJ's contact with the TCD co-op declined during the 20s, though he did retain a paternal interest in it for a time.

During this time Plunkett and the IAOS were inhabiting a different universe; the consumer movement, the Co-operative Union, was Manchester-based, and had not succeeded in making the bridge with the producers movement in Ireland. There is no record in the IAOS Annual Reports in the period 1913-1918 of any connection with consumer co-ops; they are classified as creameries, agricultural societies, credit, poultry and miscellaneous.

The Co-op Reference Library was started in Plunkett House in January 1914. The Annual Report in 1917 mentions the Library and its publication Better Business, but laments its lack of circulation. Then in June 1919 the Irish Statesman commenced, in its first existence; it incorporated the Irish Homestead, and attracted support from a galaxy of writers which included AE (who edited it), Stephen Gwynn, Henry Harrison (who had been Parnell's secretary), Paul Henry, JM Hone, Shane Leslie, Brinsley McNamara, Lord Monteagle, PS O'Hegarty, Horace Plunkett, Lennox Robinson, Lionel Smith-Gordon, James Stephens, WB and JB Yeats.

This continued up to June 1920, attracting additional writers like Erskine Childers, Captain JR White, Darrell Figgis, Aodh de Blacam and Bernard Shaw. There is no trace of any JJ contribution to this first Irish Statesman series, though he knew and socialised with many of the people concerned; he had been in Oxford with Smith-Gordon, and attended the AE soirees. I find this surprising, because JJ had been supportive of the Convention process in 1917, and had been promoting the Commonwealth solution, with James Douglas and AE; the Irish Statesman had emerged specifically with this politics. We must explore possible reasons for this. He does contribute later in the 20s, to the second series, which began in September 1923.

Published papers

I am indebted to Kate Targett of the Plunkett Foundation in Oxford for most of my father's 'co-operative movement' papers from this and later decades. The first one she found relating to JJ was published in the IAOS journal Better Business in April 1916 and is entitled 'The Problem of Agricultural Credit in India'; it was evidently recycled from JJ's Albert Kahn Travelling Fellowship report. There was a sequel in the next issue, and a further one in 1920 reviewing a book on co-operation in India. I have reviewed these three articles below.

She also found an article published in the January 1916 issue of Better Business (Vol 1 no 2) by William J O'Bryan who was the founder of the TCD Co-op, and who went on to found the Oxford one subsequently. This expounds in some depth the thinking behind the action, and it clearly was an important influence on JJ's socio-economic thinking, so it is worth reproducing in full.

Instinctively they must have realized that once the principle of co-operation, in the shape of working societies, was introduced into seats of learning, that the enemy would be attacking them at their most vulnerable point -- the coming generation. The forces of General Ignorance would soon be in a precarious position, and not at all to the liking of his wily old servant, Private Trader.

The university age appears to be the most receptive age for social ideas. It also seems about the minimum age possible for full responsible membership of a co-operative society, even if the law did not already lay down the definite age minima of 16 years old for membership and 21 years old for committee eligibility. The universities, therefore, offer in many ways the most suitable and earliest period at which the coming generation may be quickened into co-operators.

The fact that it is only the middle and upper classes who can at present afford a university education brings to the front what is perhaps the most important bearing of university co-operative societies on the co-operative movement as a whole.

Namely, university societies may supply the medium by which all classes may be included in the co-operative fold.

"For an idea to become a national idea it must have supporters in all ranks of life. It is not enough that it should have permeated this class or that. If it is opposed by other classes, or is regarded with indifference by the intellectuals and persons of education and cultivated minds, it may, indeed, achieve great things for those apply the idea. But it will never be the basis of a national civilization if the intellectuals hold aloof from it."

With the advent into the movement of wealthy purchasers, the new and insistent demand that would arise for co-operatively-produced goods, of a quality and range not yet manufactured, would induce a supply that might help to make co-operative principles of production the dominant ones in industry.

The rural and urban sides of the movement have been developed rather independently of each other, and, on the whole, by the well-to-do and the poorer classes respectively. If AE's ideal that the urban and rural organizations should become more helpful and complementary to each other is to come about, members of university societies blown by fate into every kind of life and land might supply the necessary cross-fertilization, at the same time as they bring to the movement the nourishment of a new imagination and culture of thought.

The fact that the leading members of the Dublin and Oxford University Societies, which are of the urban distributive type, have from the beginning been in active and intimate sympathy with the agricultural organizations of both countries, seems to justify this hope.

What preparations for future political strength is the movement making? Are our future rulers being trained to be co-operators? Labour's alliance is assured. But middle and upper classes are for the most part either ignorant of co-operation or are definitely the minions of the middlemen.

Here again, the value of university societies is obvious. In addition, the cumulative influence of thousands of new co-operators -- educated and influential -- is certain to affect the attitude of the general Press. Incidentally, the Press -- supporting the middlemen through the accident of advertisements -- will find that the stronger co-operation becomes, the stronger will become the necessity for the middlemen to advertise more than ever; a state of affairs which will not be unpleasing to the newspapers, and which the newspapers can hurry up. Even without a co-operative bias, the notice taken by the Press of Oxford's espousal of co-operative ideals led to keen inquiries as to starting other societies from such remote places as India, China, Africa and Germany.

Important as seems the need for all universities, old and new, to have co-operative societies, the movement itself is obviously handicapped in promoting them directly. The Co-operative Union and the various Wholesales -- the CWS, SCWS, and IAWS -- could, however, be of useful help, once the wish for a society had developed itself within a university.

The Co-operative Union (failing an organizing scheme more elaborated infra) should at least have available detailed information of the formation, working, and peculiar difficulties (with their possible solutions) of other university societies already in existence.

There is scope for the development of such minor conveniences as a special university insurance policy -- a need which is already met, but inadequately so, by a non-co-operative insurance company. The growing need for a co-operative bank with branches everywhere --in preparation for the banking ring that seems to be threatening us -- would perhaps, become a justifiable venture with such superior facilities ready to hand in the universities for tapping a fount of wealthy customers at the very beginning. their banking careers.

The Wholesales should make an effort to study and supply the new and special requirements of the university societies -- if only in preparation for the demand for first quality goods, of which the university demand is but a small advance-guard. Goods must be nothing less than London West End quality. If this demand is not met, one of the most valuable co-operative ideals will mean nothing to the new army of co-operative recruits.

I have purposely dealt at some length on a few of the influences that university societies might be expected to exercise on the co-operative movement; as, if these societies spread, the universities may become great factories, turning out from hundreds to thousands of complete co-operators every year. And this new factor in the future of co-operation must without doubt be the main point of interest to co-operative readers. It is, therefore, not necessary here to touch more than briefly on the advantages of the societies to the universities themselves.

The educational advantage is rightly the greatest. Undergraduates will not only become familiarized with an accepted solution of many of our crying social problems -- the society being a practical lesson in sociology and economics -- but an education in business methods will be afforded whose value as munition for the coming economic great war cannot any longer be ignored. Railways, banks, and other big public companies, municipal governmental enterprises, will find it difficult to uphold the present standard of respectable fatuity required by their directors and officials, when all will have passed through a shower bath of hot and cold business ideas. There is many a cobwebby old don, too, who would have been the better for an early wash !

Whether the university is composed of one or many colleges, the co-operative society might become the pivot on which the whole economic life of the university -- official and individual --- could advantageously turn. A strong "town" society would be a willing ally, to each society's advantage, in the matter of coal, bread, meat, and other official requirements, and would meet members' individual requirements in the matter of goods not undertaken by the "gown" society. Such an arrangement was satisfactorily initiated at Oxford. The economic organizing of the university, when thoroughly carried out, should finally lower appreciably the cost of living in the university. Lastly -- if I may again quote AE -- "The leaders of the next generation are, in all probability, now in one or other of the universities, and that seat of learning which can best educate its students to have sympathy with, and understanding of, great popular

movements, and of the problems of national economics, will have the greatest intellectual influence in the future."

The general constitution of Dublin and Oxford University Co-operative Societies needs little description here, being of a form familiar to the majority of co-operators. The two societies adopted the "General Rules for an Industrial and Provident Productive Society" (Form 2P and 3P respectively), compiled by the Co-operative Union. Both societies are, of course, affiliated to the Union.

In addition, Dublin (registered 25th July, 1913) is affiliated to the IAWS, and Oxford (registered 18th May 1914) to the CWS. The conditions peculiar to a university are provided for in over twenty "Special Rules" in each case. The shares, nominally £1, are transferable only, but the committees have the power and discretion of repaying any shares of members leaving the universities. Membership is unlimited, provided the applicants are connected with universities. The principle, of profit-sharing for employees is embodied. The 0UCS has a rule that "Not less than four-fifths of the members of committee [of twenty-five] shall be members of the university in statu pupillari". This rule was designed so that the running of the society, with its valuable education, should not gradually, by mistaken zeal, perhaps, be taken of the hands of the ever-learning and ever-changing undergraduates. Each society is avowedly out to further the spread of co-operation -- including in a special manner, of course, help in starting societies in other universities -- and to promote the use, wherever practicable, of goods produced co-operatively and at home.

Under pre-war conditions, both societies succeeded even beyond the sanguine expectations of their promoters. Both, however, were paralysed -- obviously through no fault of the system -- on the outbreak of war, when their undergraduate members almost to a man answered a communal call of a greater degree.

Increasing numbers of the dons and fellows left behind have conscientiously tried to do their duty to those fighting for them, by supporting in a practical way -- they are morally trustees -- the young societies left fatherless. In simple words, it is just the difference due between the duties of dying and buying. I do not think the trust will be misplaced. The societies will survive the war and -- many of their members -- young as the societies still will be.

With a society well established under normal and peaceful conditions, many useful developments will be possible. Enterprise should never be lacking in a university society, supplied with a continuous stream of fresh blood always trying to find new veins and arteries to flow along.

For instance, outgoing members generally have a quantity of articles -- books, furniture, &c -- which they wish to dispose of, and which incoming members are as wishful to buy. An auction store room, run by the society, would at least save each side being robbed twice over. A co-operative restaurant might also be undertaken. These two projects were, in fact, on the original programme of the DUCS. Some universities might find more scope for co-operative lodgings. Alert minds in the different universities will not be slow to think out suitable developments.

When other societies come into existence, or even before, a federation of university societies would have much to commend it. It might conceivably take the form of a special university department of the Co-operative Union, or the university societies might undertake its duties turn about.

The functions of the federation could, perhaps, be follows:-- The publishing of a periodical bulletin, containing the balance sheets, reports of meetings, new developments, experiences and progress of the several societies, with suggestions and other apposite information. This bulletin could give in full what could at most only be summarized in The Homestead and The Co-operative News.

Special university propaganda, with suitable leaflets and literature, should be available. Voluntary organizers would not be lacking. The federation would represent organized university opinion in such matters as the demand for superior co-operative productions, and to the Wholesales a definite organised demand would be a tremendous help.

The federation might see to the preparation every summer term of general evangelizing matter for the various school magazines, so that the thousands of boys leaving the school for the universities should become new members on their arrival. Influential "old boys" can always have such matter inserted. The 0UCS carried out this scheme itself in 1914.

Members who have been keen and have done good work during their university careers would probably welcome an opportunity to continue their help; and they should not be lost sight of. If their final settling-places were methodically noted, the movement through the Co-operative Union and the University Federation might come to have a kind of consular service or an intelligence department with agents all over the Empire, further co-operation. Wealthy societies at Oxford or Cambridge might quite likely embark on some form of self-supporting club house with bedrooms, &c., in London.

Through the common federation the use of these amenities might be extended to members of other university societies when they would have occasion to be in London. Reciprocally, club rooms in every university town should hospitably be available for co-operators from other universities.

These ideas and hopes for university co-operative societies may seem fanciful; but many more wonderful things have come to pass, and will come to pass, in the movement started by the weavers of Rochdale.

The foregoing, and indeed the India material reproduced below, must have been in the pipeline prior to the 1916 rising, and JJ would have been committed to arrangements to pursue his interest in the economics of co-operation via the residual credit available to him from the Albert Kahn Foundation. This he used in the autumn of 1916 for his trip to France which enabled him to publish his 'Food Production in France in Time of War'.

I have embedded this in the Albert Kahn sequence, but it is also relevant here; it was reviewed by AE in the Irish Homestead (see below), and also in Better Business (Vol 2 no 2 Feb 1917) by one LSG. This review is somewhat grudging; he accuses JJ of possessing '..strong political views..' and regards the title as misleading. He does however note that '...he has had the insight to realise the serious importance which agricultural organisation plays in the whole structure..', and urges people to buy the pamphlet, concluding that '...where France thinks nationally and organises parochially, we organise nationally and think -- very parochially'.

There are probably few countries in Europe where the value of organisation for industrial purposes is less understood than Ireland. Outside the co-operative movement Irish agriculture is a chaos of individualism, and our Press and public men for reasons which are not inscrutable have, as a general rule, opposed any change in business methods, and when necessity arises, and the industry must be organised somehow to bring about increased production, those in authority show their inexperience and lack of grip. We do not intend to rake up the past, for the best thing we can do is to do the most we can with the machinery now available.

But we ought to be storing up wisdom from past errors so that we will not blunder in future. Nothing could be more interesting than to compare Irish methods of organisation with those adopted in foreign countries where the necessity for increased food production was immediately realised after the outbreak of war. By comparing their methods and our own we may be taught by experience at last to arrive at sound ideas. We will be helped in this by a perusal of "Food Production in France in Time of War" (by Joseph Johnston MA FTCD, Dublin, Maunsel and Co, Price 6d) a most interesting and thoughtful pamphlet, (the author of which) went to France last year.specially to investigate the methods of organisation there.

Mr Johnston has found it impossible to make clear the French schemes for agricultural production without giving an account of local government in France, its relation to the State.and central authorities, comparing it for efficiency and adaptability with our own system of local government, and this also is interesting and valuable, because we see that there was an official machinery capable of instant co-ordinated action when there was need.

In fact, in France the machinery of local government was as ready as the army for instant action in time of war. In these countries it took nearly two years to create an entirely new military machinery, and the State has not even begun any readjustment of the machinery of local government to the obvious needs of the nation.

We are not concerned so much with the machinery. of local.government in France as with the methods employed in a country depleted of men to maintain the food supply. Mr Johnston tells us that after the declaration of war steps were taken to make up the deficiency of labour by the introduction of labour-saving machinery. As the purchase of power machinery by the small French farmer.was uneconomic, it was necessary to adopt co-operative or communal methods, and here the French Government reaped the reward of its long encouragement of agricultural cooperation. It had the economic machinery ready for use and capable of expansion.

These societies were found invaluable as a means of spreading the use of labour-saving implements. Where co-operative societies did not exist, the commune or parish was required to create an agricultural committee and practically to turn itself into a co-operative association. By a decree of the Minister of Agriculture, subsidies to the amount of one-third of the cost of the new plant were offered to co-operative societies or communal committees buying labour-saving machinery for collective use.

Mr Johnston saw these machines at work. A tractor plough driven by a discharged soldier who had lost a foot was doing as much work as four men and eight horses could have done in the ordinary way. The commune or co-operative society paid for labour and running expenses, and hired the tractor for ploughing at the rate of one pound per acre. The General Council of the Department, a body corresponding somewhat to our County Councils, had voted fifty thousand francs to be used as loans to be spent in procuring machines.

The railway companies, our Irish companies might take note, carried tractors and those who taught their use to the.scene of demonstration free. Some companies when societies ordered these machines gave reduced rates for carriage. They were wise, hoping for an ultimate return and increased traffic receipts for carrying a greater bulk of agricultural produce. We have yet to hear of an Irish railway company giving any special facilities to those engaged in creating new trade or in the work of instruction. Our railway companies throw on the outsider the sole cost of creating the very trade by which the companies profit.

The French commune or parish is the ideal unit for the purposes of.agricultural organisation. It is not too large like a County Council. It covers an area like that naturally covered by one of our own cooperative dairy or agricultural societies, the natural area. for a group of people who all know each other, have personal relations with each other, and find it convenient to walk to a common centre.

If the area is increased, personal interest decreases, and that is the reason why we have always held that the co-operative society rather that the County Council was the true unit for the State to deal with where agriculture was concerned. This question of the natural area for a social organism has not met here the consideration it deserves.

The ancient Greeks had a wisdom in their theory that a state should not contain more citizens than could be influenced by the voice of a single orator. They realised that certain developments were made possible by intimacy and personal relations which were impossible where the area and population were so large that that complete knowledge was impossible, and therefore complete trust was also impossible, and so there was more sluggish and less confident action.

In France at the present time the whole agricultural policy is dominated by co-operative or communal committees acting in conjunction with the Director of Agricultural Services. In Ireland there is no such clear policy, and no such adaptable machinery is relied on. As Mr Johnston points out, the County Committees of Agriculture, however useful in supervising the schemes for agricultural education, are useless when it comes to business or practical economic enterprises like buying.

Another thing, too, is against them. The fact is that the County Councils have not even a majority of agriculturalists on them, and to set such bodies to develop agriculture,is like setting a mixed body of lawyers, doctors, and farmers, with a small percentage of engineers, to supervise and develop some great engineering enterprise which required an altogether expert direction and.not a mixed committee at all, and where the admixture of doctors and lawyers was only a hindrance to efficiency.

Mr Johnston tells us that the French did riot announce their agricultural policy until they had created the conditions which made it possible to carry out the policy. For a continued agricultural production, what was required was expert.direction, labour, capital, implements, seeds, and fertilisers. None but practical farmers were appointed on these committees. The Government used all their prisoners of war, and let loose men from the army to aid in the main agricultural operations. It give illustrations in every commune of what labour-saving machinery would accomplish.

The agricultural credit system in France was well developed, and nearly every commune had its agricultural bank, worked on cooperative lines, and these local banks were able to get what money they required from the regional banks, which again drew on the Bank of France, which under its charter is bound to give advances up to fifty million francs free of interest to these regional banks, and, further, the State requires that one-eighth of the profits made by the Bank of France in discounting agricultural paper should be paid to the State, and the money thus used is earmarked for further loans free of interest. The amount thus placed at the disposal of agriculture was a few years ago one hundred ant three million francs.

The machinery of co-operative credit is still working, and the Government had agencies in existence which were capable of supplying most of the requirements of the farming population. The local committees had.power to requisition the use of machines and implements in abandoned farms when all the workers were called up for the army, and these were used by the commune.

These committees also undertook the cultivation of land where the owners, by reason of age, or none being left to work, could not undertake the cultivation themselves. After deducting the cost of raw materials, labour, etc., the net returns are handed over to the land owners. The object was to increase the volume of food production, and nothing was allowed to stand in the way.

Those who study Mr Johnston's pamphlet will see the extraordinary benefit of agricultural co-operative societies in every parish. The social machinery for the State to use was ready to hand. Little had to be improvised. The problems of organisation had been thought out, and there was nothing of the state of things which our rulers so proudly acclaim as a capacity for 'muddling through'.

The scheme in operation in France was practically identical with a policy we advocated two years ago and which was possible in Ireland if there had been any clear thinking by our rulers. We have got a very inferior scheme. Nobody knows who to deal with. T'he greatest confusion prevails among farmers. We will be lucky however, if from the muddle we now are in we learn the necessity of organisation and of clear thinking, and above all of care for national interests, so that they shall not be sacrificed for the benefit of a small section of agricultural middlemen, as has been the case in Ireland.

There was a sequel in Better Business, Vol 1 no 4, July 1916, entitled 'Co-operative Credit in India'. In this JJ credits the Madras Government with sending in 1892 one Frederick Nicholson (later knighted) on a roving commission to Europe to study agricultural credit. He encountered the IAOS on his travels and was suitably impressed, reporting on the Raffeisen system in 1897 and 99; it was soon realised by the Government that legislation would be necessary; the Co-operative Credit Societies Act was passed in 1904 when Lord Curzon was Viceroy, and updated in 1912.

JJ castigates, in passing, the British Government in Ireland for not updating the 1896 Friendly Societies Act to meet the requirements of the Irish co-operative movement, evaluating the updated Indian legislation as superior, as it encourages the development of co-operative credit and banking.

In Better Business May 1920 (Vol 5 no 3) JJ wrote a review of HW Wolff's 'Co-operation in India (London, Thacker, 1919). In it he refers back to his 1916 articles on the same topic, which it seems drew Wolff's attention to India, the latter referring to JJ as 'Johnston Pasha', to JJ's amusement. He welcomes the book as a useful comparative international study, and comments his emphasis on the role of co-operative credit and banking, contrasting this with capitalist banking which always looks primarily to property as security, rather than social organisation.

Wolfe credits the Oxford students' co-op as having been a model for Indian student co-operative initiatives. This had been founded by WJ Bryan who had gone to Oxford from Trinity, where JJ credits him as being the founder of the TCD student's co-op in 1913. JJ therefore reproves Wolff for regarding 'Oxford (as) leading the way' in student co-operative retailing.

It is evident from the foregoing that JJ all during the decade dominated by the 1916 Rising was focusing on the problem of democracy in economic organisation, and he regarded the TCD co-op as a significant pilot project in consumer co-operation, to be integrated with a food production system organised co-operatively, and supported by co-operative credit.

He also regarded the TCD co-op as potentially a working model of a commercial operation, of use in the context of the School of Commerce which he aspired to have the College set up. This emerges in a subsequent (1921) paper in Better Business, summarised in the following module.

Copyright Dr Roy Johnston 1999

University Co-operative Societies (WJ O'Bryan Jan 1916)

"Delicious Degrees given away with a pound of Tea". Such was a jewel of humour in a cartoon that appeared in a certain gombeen newspaper, when the Dublin University Co-operative Society was first publicly announced. And the horror and hostility shown by the same Press in conjunction with its masters, the Dublin middlemen -- who were, in a way, peculiarly qualified to prophesy -- was perhaps the most hopeful compliment that could have been paid to Trinity's pioneer society. The 'Homestead' Review of JJ's 'Food Production in France'

This review, unsigned and therefore probably by the Editor George Russell (AE), was published on November 24, 1917, under the title 'The Country of Clear Thinkers'.

Co-operation in India

In this article (Better Business April 1916) JJ shows how in the traditional village commune the 'bania' had fulfilled a role analogous to the manager of the co-op, but then when British laws came in, the commune role was ignored; the State dealt only with the individual, who was regarded as the owner of a plot of land hitherto assigned by custom from the commune. The 'bania' was transformed from 'co-op manager' into 'gombeen middleman', and the producers became dependent on moneylenders, who being literate had no problem forging documents to bring their victims to court, and charging interest rates of 75% or more. JJ gives anecdotal evidence of how this worked, in the form of a case involving the murder of a moneylender, from the experience of his elder brother James, then a judge.

[1910s Overview]

Some navigational notes:

A highlighted number brings up a footnote or a reference. A highlighted word hotlinks to another document (chapter, appendix, table of contents, whatever). In general, if you click on the 'Back' button it will bring to to the point of departure in the document from which you came.