Irish Associationfor cultural, economic and social relations |

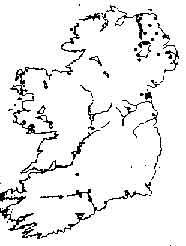

CELTIC IRELAND AND OTHER FABLES: POLITICS AND PREHISTORYRichard WarnerBased on a talk given to the Annual Conference of the Irish Association, Carrickfergus, 12-14 November 1999 It is virtually a received truth that the Irish are a Celtic people as are, so we are told, the Welsh, the Cornish, the Bretons and the Scots. Indeed a few years ago the President of the European Commission, on opening an exhibition on the Celts in Venice, announced that being Celtic was the common bond that drew together all the nations of the European Economic Community. What utter hogwash! It is only a short step from such politically contrived pseudo-historical nonsense to Himmler's warning to German archaeologists and historians that 'the only thing that matters to us, and the thing that [archaeologists and historians] are paid for by the state, is to have ideas of history that strengthen our people in their necessary national pride'. We have our primary, indeed only, information on the Celts as a named people or group (Celtae, Keltoi) from Classical authors such as Herodotus, Posidonius and Caesar. From these we learn that they were a warrior people not necessarily a homogeneous race or an ethnic group, perhaps an elite or a caste who lived in central Europe north of the Alps, but whose influence was felt widely over Continental Europe. They were, so the Classical authors tell us, warlike, tall, blue-eyed, muscular one is reminded rather more of the Nazi stereotype of the pure Aryan than of the typical western Irishman! Modern scholars base their categorisation on all sorts of evidence it might be language (for linguists), pots and brooches (for archaeologists) or head-shape (for physical anthropologists). The results of such exercises are seldom reconcilable one with another. All the more reason for doubting the wisdom of labelling groups, identified by selective evidence, with names used by ancient writers whose methodology of classification was different again and is, in most cases, unknown. The Classical writers gave us place-names and personal names within the Celtic areas they identified, and nineteenth-century linguists found that these names belonged to a common language, which they unsurprisingly called 'Celtic'. Furthermore they noted that these names were to be found at the same period (the few centuries just before and just after Christ what archaeologists call the Iron Age) over a wider area than that in which the contemporary authors had located the Celts. The assumption was that the Celts were extremely widespread and there was almost a Celtic 'empire', all the inhabitants of which may be called Celts. This was compounded by the work of archaeologists, who located variants of a distinctive artefact culture, which they called the 'La-Tθne' culture, over much the same area. Some early place-names and archaeological material in Ireland belonged, as was quickly noted, to these groups and as a result Ireland found itself in this scholastically defined 'Celtic empire'. A cautious archaeologist might have paused, before assigning an ancient name to a whole people on the basis of some objects and place-names perhaps noting that other objects and place-names in the same area did not actually belong to the 'Celtic' language or the La Tθne culture. No such caution prevented Ireland, in its Iron Age phase, from being called 'Celtic'. The next step in the 'Celticisation' of Ireland is extraordinary. According to the orthodoxy, the Romans failed to invade Ireland or to influence it in any great degree. Therefore it follows that the people of the Early Christian period, notwithstanding the social impact of Christianity, must also have been Celts. Furthermore it can be shown that the language of at least the learned Irish in the Early period (and of all the Irish in later times) is a descendant, of sorts, of that earlier tongue defined as 'Celtic' by the linguists. Clearly, then, if we follow this approach, Ireland was a Celtic country and the Irish a Celtic people until the coming of the English. So the archaeology of the Early Christian period may also be called 'Celtic', giving us Celtic manuscripts, art, crosses and so on. Even the most extreme nationalist is unable to deny the reality of the various English invasions over several centuries, but by some sort of suspension of logic it is widely believed that English blood does not surge sufficiently in Irish veins to modify whatever previously flowed. So, if the Iron Age Irish were Celts so must modern Irishmen be. How on earth, one wonders, did so many patriotic Irishmen manage to acquire English surnames Adams, Pearse, Collins for instance while retaining their pure Celtic blood? An archaeologist, if forced to assign a single label to an area, will base it on the sum of the archaeological evidence. He will look for consistency, define a culture. If he wishes to argue that this culture was a variant of one found elsewhere, he must show that there are more similarities than differences between the two material assemblages. What happens when we look at the Irish Iron Age with a critical eye? In the first place we find that many aspects of the Continental La Tθne culture, particularly those that relate to the mass of ordinary people settlements, hillforts, pottery for instance do not appear in the Continental form, if they appear at all, in Ireland. We find, rather, that the La Tθne elements in Irish archaeology are confined to the weapons and baubles of a small, probably warrior, elite. Indeed, as can be seen on Figure 1, a smaller total area is dominated by such elements (diagonally shaded areas) than the area in which they are rare or absent. We find indeed that major, often high-status, elements of Irish Iron Age culture burial rites and ritual sites for instance even in the areas in which the 'Celtic' types are common find no parallel in the Continental Celtic world but have evolved within Ireland. Navan, in other words, is not a Celtic but a native Irish ritual monument.

Figure 1: Map of Iron Age 'cultural' areas as defined by archaeological material. Only in the diagonally shaded areas is there a significant propostion of 'Celtic' material. To illustrate this claim I offer Figure 2 a high-status man of the latter period reconstructed from literary and archaeological evidence, a warrior living in a society that many writers insist on describing as 'Celtic'. He wears a cloak of Roman form, probably died purple in the Roman fashion. His sword is derived from a short legionary sword even its name in Irish is derived from the Latin. His small round shield is derived either from the late Roman army shield or (less likely) from a much earlier Irish Late Bronze Age shield. We lack Irish Iron Age shields but we can say that the great oval shields of the Continental Celtic warriors were nothing like this. His brooch is derived from a Romano-British army brooch. His tunic is named after the Latin for its material. In short, he has absolutely nothing culturally Celtic about him he ought to be labelled Roman!

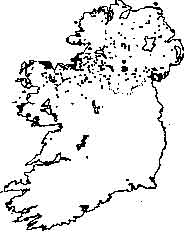

Figure 2: Drawing of an Early Christian Irish aristocrat, reconstructed from archaeological and literary evidence. Does it really matter that many people, not only those with a political agenda, are misusing history? I think it does. Northern and western Europe contain a number of nations who share, and have shared historically, certain common traits, including languages and archaeological cultures, some of which can be traced back to the Germani. These nations and their languages and cultures have long been referred to by scholars as Germanic, the parallel with the case of the Celts being obvious, and thus the concept of a greater Germany became a central tenet of a terrible dictatorship. Himmler again 'Prehistory is the doctrine of the eminence of the Germans at the dawn of civilisation'. In Ireland archaeological inference has not infrequently been the slave of political correctness. I give some examples. Figure 3 is a map of artefacts belonging to the earliest inhabitants of Ireland (or at least the earliest we know of). Quite clearly the distribution implies that the first 'Irishmen' settled in the north-east. For many years after this was proven, and internationally accepted, it was denied by influential archaeologists teaching in Dublin.

Figure 3: Map showing sites where early mesolithic material has been found.

Figure 4: Map of Neolithic Court Tombs. It is not unacceptable to be proud of one's past. The eminent archaeologist Graham Clarke observed many years ago that 'in Ireland .. the outcome [of independence] has been a splendid outburst of archaeological activity, flattering to the prestige of the country and .. stimulating those .. feelings of attachment to the past which make for national unity and heighten the sense of national consciousness'. He also attacked the totalitarian manipulation of history for political ends in Germany and Russia where 'the subject has been deliberately harnessed to subserve the interests of the state without any necessary regard for objective truth'. I suppose the distinction is that the similar attitudes were rather differently put into practice. The blatantly sectional interpretations of the Irish past noted above are less likely to be heard from academics today, but echoes of political orthodoxy can still be found. A few years ago I suggested, against current opinion, that there was probably an invasion of Ireland from Roman Britain. My suggestion caused an enormous controversy, and was almost completely rejected by my southern colleagues. Curiously when I lectured on the subject, in the Republic, to what one might describe as ordinary folk, my audiences had no problem with the thesis. Now of course there is no earthly reason why my southern colleagues should accept my interpretation of the evidence, and had their objections been purely archaeological I would have been delighted to argue. But an editorial by a Dublin archaeologist, in an Irish archaeological magazine, suggested that other agendas were at work 'This is a time of great sensitivity in the present relationship between the islands of Ireland and Britain.. In this context it is perhaps unhelpful that coverage is concentrated on the notion that .... Ireland was, after all, part of the Roman Empire. Within this new mythology it does not take too much of a leap of imagination to see how such a formulation could be used in political agendas today'. In other words 'archaeology should subserve the interests of the state without any regard for objective truth'. In fairness, I must admit that the Romano-British thesis could not come from a worse source than an English archaeologist working in Belfast and, were it not for the dangers in our society, I would be amused by the accusation from a Dublin colleague that I was 'a stooge of MI5' and that my thesis was part of a plot to 'destabilise Irish politics'. The examples of censorship have come from the academics themselves, with no overt pressure upon them from politicians. Such pressure may exist almost certainly does but I am unaware of it except where I have been the recipient. A few years ago, shortly after the Ulster Museum opened a new gallery dedicated to Irish prehistory, I received a letter from a Belfast MP, now an MLA, criticising us for not referring to the Cruthin. These were an Early Christian Ulster people who have been dragooned into service as the ancestors of all good Ulster Protestants, long predating the upstart Gaels (that is, Catholics). Although a very small number of scholars have given their blessing to this fiction, it is the peripheral wannabees who are in the vanguard of the new Pictish movement. The unionist writer David Hume echoes an increasingly popular myth when he writes that 'the ancient history of Ulster .. underlines the essential fact which Irish nationalists conveniently ignore: Ulster has always been different from the rest of Ireland. And it always will be'. With reference to those archaeologists and historians who have had the temerity to question this unsupportable claim, Ian Adamson has observed that there is a 'persistence of Gaelic patriotic racialism among an important sector of our academic elite, whose political influence among the educationalists and media has been profound'. My word! A 'stooge of MI5' and a 'Gaelic racialist'. At least I can be proud that my influence has been profound. As I see it the danger to objective truth in Ireland, particularly in the North, comes not only from those with strong agendas. It comes also from liberals (and I include here the Northern Ireland Office) who appear to believe that cultural sensibilities are too fragile to face authoritative contra-opinion. We are also seeing evidence for instance cultural agencies subsidising propaganda masquerading as scholarship or literature of objective truth becoming a victim to political correctness and to 'parity of esteem'. We are entering a new totalitarianism the dictatorship of sensitivity. Footnote: the following appeared as editorial comment in a popular Irish archaeological magazine shortly after my lecture to the Irish Association, and was based on a newspaper report of the conference. 'Perhaps the authorities in Ireland should be cautious about allowing archaeological material to fall into the hands of archaeologists who appear to cling to the dangerous racial prejudices which typified twentieth-century Europe.' In case the reader might suppose that this writer is agreeing with my thesis and opposing the political use of such terms as Celtic, I must complete the quotation. '..the Irish Association for Cultural, Economic and Social Relations, if it entertains Warner's proposals, should drop the adjective 'Irish' from its title.' Richard Warner has been on the staff of the Ulster Museum since the 1960s, where he has been Keeper of Antiquities since 1988. He has worked extensively on the archaeology of Iron Age Ireland.

Some navigational notes:In most browsers, if you click on the 'Back' button, it will bring to to the point of departure in the document from which you came. Navigation options are given at the foot of each page, thus:This page has been re-edited for the Web by Dr Roy Johnston on November 13 2000 |