Nosokinetics

Straightforward discharges are like axial flow:

Carl Long vs Editor

The discussion continues; Carl Long writes: Time must come in to the equation since we are considering 'flows'. I had a funny thought walking past a stream with my little boy. Straightforward discharges are like axial flow - nice and smooth as in the centre stream. Out in the peripheries 'eddy currents' occur and things like branches get stuck. In essence patients 'out of the centre' i.e. those who don't fit the ‘discharge as soon as possible mould’ get stuck. What do you think? Maybe flow mechanics would help unblock the system.

Editor replies: Axial river flow, an interesting thought. It reminded me of my youth hiring out skiffs on the river Arun. The Arun is the second fastest river in England; the tidal drop is 16 feet. Rowing with the tide is simple; rowing against it requires local knowledge and skill. The secret is to take advantage of the reverse flow, tuck into the sides in the straights and to cross at the bends to the short side. Easy if you know how.

Sometimes people need a helping hand. This is where policies based on guidelines and patient choice fall short. Medicine is both an art and a science. Although we told the tourists what to do, coming back with the tide many missed the landing stage and went through the bridge. So we had to row them back.

‘Stuck branches’ brings back memories of my early years at St. George’s hospital, when we changed a geriatric medical service with a waiting list of 68 into a no waiting list service by creating therapeutic environments. Given appropriate care, time to regain fitness, optimistic staff and supportive after care many ‘bed-blockers’ returned home The picture illustrating the basic principles of stroke patient nursing care was shot in 1973.

Figure 1. Rather than nurses doing everything for bed bound patients, the pioneers of geriatric medicine enabled patients to help themselves, by lowering the beds and encouraging nurses to standing by while patients dressed themselves.

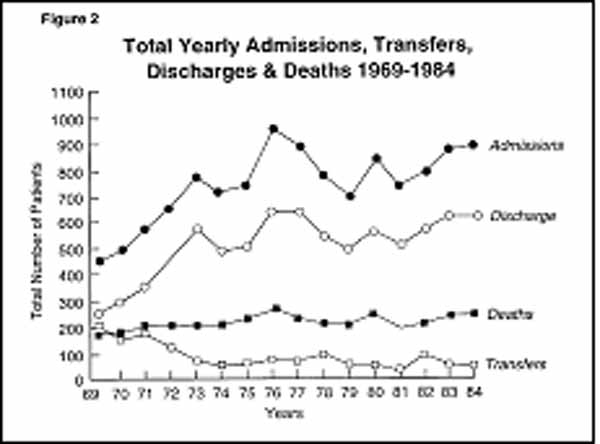

Figure 2 shows how admissions increased between 1969 and 1977, as we changed nursing and medical practice in a department of geriatric medicine.

However success was short lived; after 1977 decreased for four years before stabilizing and rising again. At first I though that we had gained a skill and then lost it. A new consultant joined in 1974 and another in 1979. Maybe they were not as skilful as I. Paranoia. Yet this explanation did not fit the data.

Figure 3. Annual admissions, discharges, transfers and deaths changed between 1969 and 1984 in a department of geriatric medicine with 186 beds serving a catchment population of 25,000 people aged 65 and over.

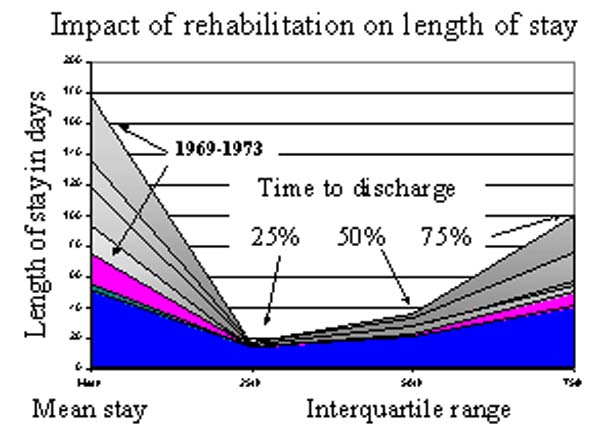

However, the percentile distribution did not support that conclusion. Figure 3 shows how the percentile distribution of the length of stay data changed. (see page 1 of the August 2004 issue for the numerical values of figure 3).

Clearly, between 1969 and 1973, when the new rehabilitative style of patient management was introduced, the numerical values of the interquartile range changed.. However, from then on they remain relatively constant, so changing staff discharge behaviour could not explain the decrease in admissions that occurred after 1977. Eventually we realised that a decision to change the use of 12 beds from admission to long-stay collapsed the service.

It’s all a question of time. Given the average stay in acute beds is 28 days, change of use of 12 beds from acute care to long-stay will cause annual admissions to decrease by 156 (13 x 12) i.e. when Ac > Lv then the ability to admit decreases. Taking your analogy of axial flow, the system collapses because more branches got stuck on the banks.

Some navigational notes:

A highlighted number may bring up a footnote or a reference. A highlighted word hotlinks to another document (chapter, appendix, table of contents, whatever). In general, if you click on the 'Back' button it will bring to to the point of departure in the document from which you came.Copyright (c)Roy Johnston, Peter Millard, 2005, for e-version; content is author's copyright,