Welfare state to welfare market

Part 1 How socio-economic decisions created and changed the NHS

(c) Dr Chooi Lee, 2005, Consultant Physician, Kingston Hospital, Surrey, England and Peter Millard

(comments to chooi.lee@kingstonhospital.nhd.uk)

History is important

In the 15th century monks looked after the chronic sick and poor. After the fall of the monasteries, means testing and residential qualifications were introduced when parishes became responsible for their care. By the 20th Century local government provided hospitals for acute illness, psychiatry and infectious diseases, and institutional care for learning disabilities, chronic illness and older people.

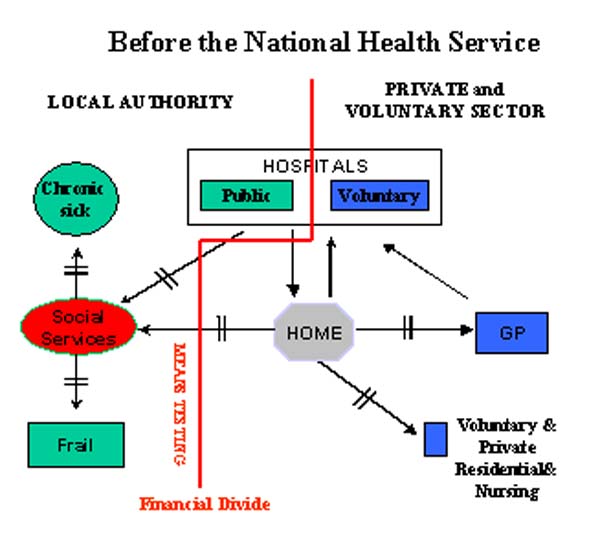

Figure 1. From the 16th Century to 1948 a financial divide separated rich from poor.

Before the NHS was created, a financial divide separated the rich from the poor. Hospital patients paid according to their means. Many GP’s were paid in kind. The two lines (¦) on the directional arrows in Figure 1 indicate rate-limiting steps, based on ability to pay and / or resource availability.

Creating the NHS

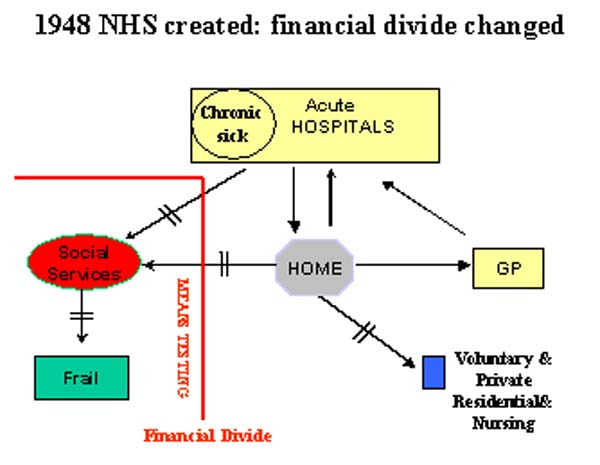

Figure 2 shows how the NHS legislation changed the financial divide. The inclusion in the 1946 legislation of free care for chronic illness was a unique feature of the NHS that distinguished it from all other countries in the world.

Figure 2 The NHS plan changes the financial divide, so the attack on bed rest can

begin.

Figure 2 The NHS plan changes the financial divide, so the attack on bed rest can

begin.Operational Planning, the NHS and Rehabilitation were by-products of war. Consultant leadership in the diagnosis and rehabilitative management of patient care in the long-stay wards was introduced, because it was hypothesised that this would free thousands of hospital beds for others to use.

Rehabilitation begins in the chronic sick wards

In 1950, 50,000 people were on the chronic sick waiting list. As the consultant led attack on bed rest began, gradually a trickle of discharges became a flood.

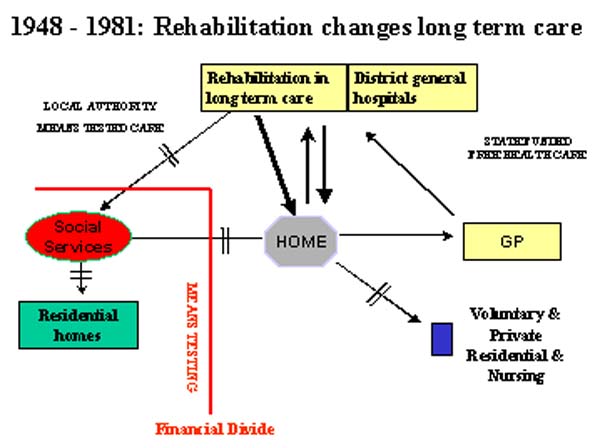

Figure 3. Gradually a trickle of discharges became a flood.

All services had to be developed. Pre-admission home assessment, out patient clinics, halfway houses, day hospitals and progressive patient care were introduced. By 1970 Districts without active geriatric services were considered to be disadvantaged.

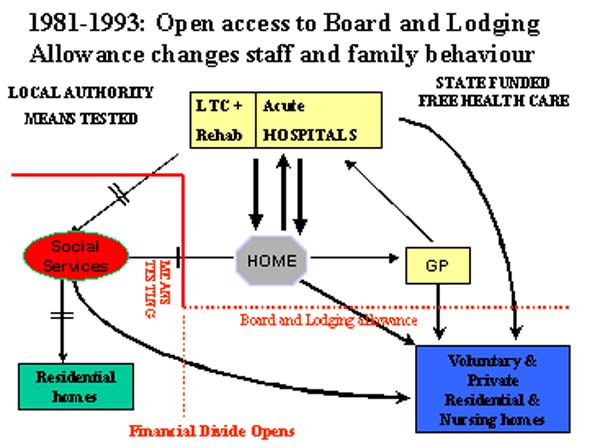

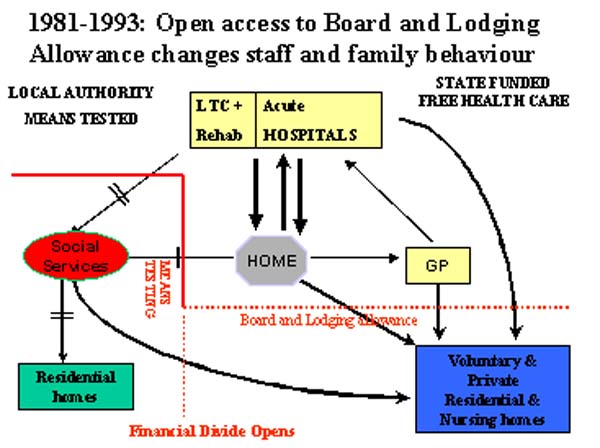

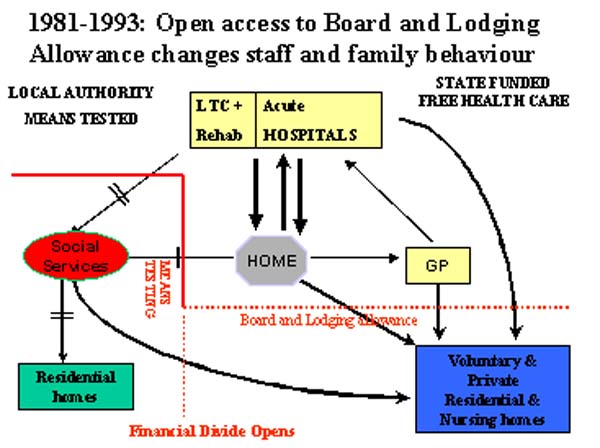

Figure 4. Open access to Board and Lodging Allowance changes staff and family behaviour.

In 1971 the bed norm for geriatrics was 10 beds per 1000 over 65 years, with 50% in general hospitals. Age related, needs related and integrated admission policies were developed, all had in common slow-stream rehabilitation.

Financial divide opens: all change

During the 1980’s and early 1990’s, open access to Board and Lodging Allowance in residential and nursing care was allowed, while strict cash limits were imposed on hospital and local authority expenditure (Figure 4). Everyone took advantage. Thousands of extra nursing home and residential beds were opened and beds for geriatric medicine and psycho geriatrics were closed.

Figure 5. Impact of government policies on bed numbers in the NHS and in residential and nursing homes: 1955 -2000.

Slow-stream rehabilitation and community support was no longer needed. Thousands of older people entered residential and nursing homes without multi-disciplinary assessment. A national audit found that 42% of nursing homes residents admitted from hospitals and 94% from the community did not have a specialist geriatric assessment(1).

Shutting the door

Government expenditure was out of control: £8 million in 1980, £2.4 billion in 1990. On April 1st 1993 open access to public funds for residential and nursing home care ceased and means testing by local authorities returned, this time as purchasers not providers of nursing care.

Figure 6. Means testing returns: 16th C controls return.

At first, the impact of the change was masked, because Social Service departments were given transition grants to purchase care. However as the hospital bed crises returned, in 1995 government rediscovered rehabilitation (HSG 95/8).

Conclusion of Part One.

When changes in parts of the health and social care system are proposed, the immediate and long-term effect on the total system of care should be modelled. The NHS experience teaches that changes made outside acute hospitals can have beneficial or adverse impact on acute hospital care. Furthermore, it shows that comprehensive services to meet the needs of dependent and vulnerable people are not required, if uncontrolled access is given to publicly funded long-term care.Part 2, introduces the biochemistry of care, considers the special needs of vulnerable older people and concludes that a new service ‘xyz’ should arise from the ashes of the past.

1.Victor, C., I. R. Hastie, et al. (2001). "The inappropriate placement of older people in nursing homes in England and Wales: a national audit." Quality in Ageing - Policy, Practice and Research 2(1): 16-25.

Some navigational notes:

A highlighted number brings up a footnote or a reference. A highlighted word hotlinks to another document (chapter, appendix, table of contents, whatever). In general, if you click on the 'Back' button it will bring to to the point of departure in the document from which you came.Copyright Roy Johnston, Peter Millard 2005 for e-version.