Nosokinetics

Welfare state to welfare market:

Dr. Chooi Lee, Consultant Physician, Kingston Hospital, Surrey, England

Part 2 Here and now and beyond

The biochemistry of care

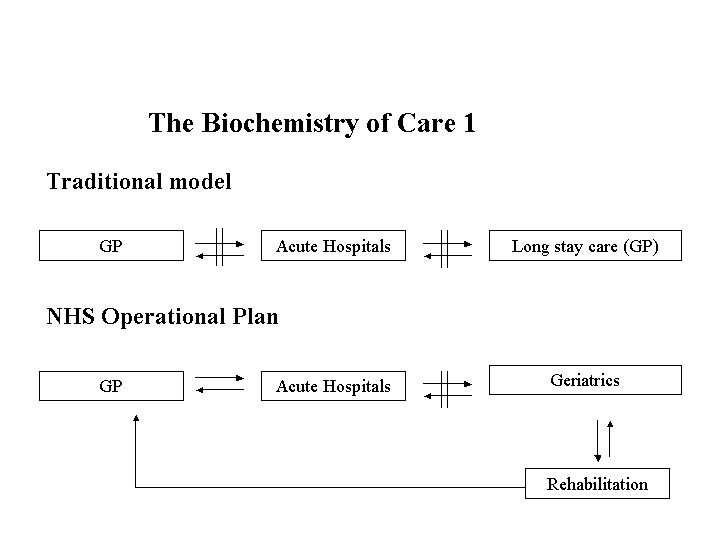

In biochemical reactions, flow is reversible. The predominant direction of flow will depend on the rate-limiting step and the availability of the end-product.Figure 1 shows patient flow before and after the NHS. In pre-NHS care, the rate-limiting step was between the GPs and the acute hospitals, and between acute hospitals and long stay care. Post 1948, because of the large numbers of people on the chronic sick waiting list, consultant physician responsibility for diagnosis and rehabilitation was introduced into long stay care. First a trickle, then a flood of patients was discharged from long stay care, and the rate-limiting steps began to disappear.

Figure 1. Four ‘biochemical’ flow models showing impact of policy change on rehabilitation within the NHS.

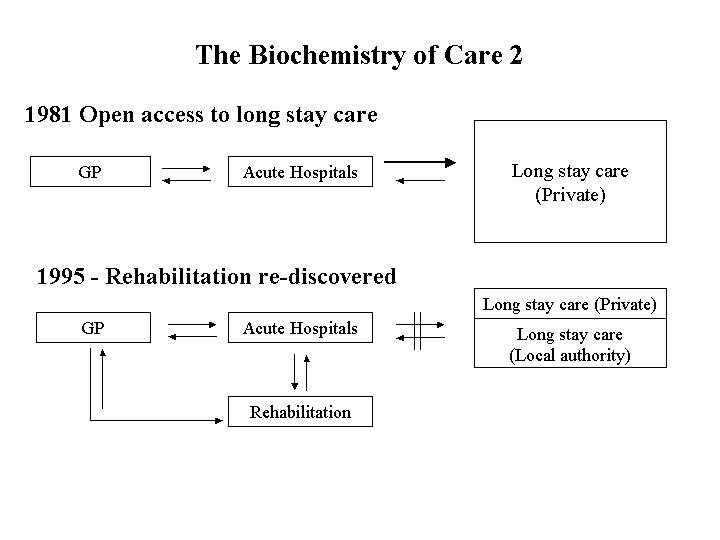

Figure 2 shows how patient flow was affected in the 1980's and early 1990's when open access was allowed to Board and Lodging Allowance in residential and nursing home care.

Figure 2. Average daily available beds in acute hospitals: Great Britain 1959-1995

Real-life priorities for acute hospitals

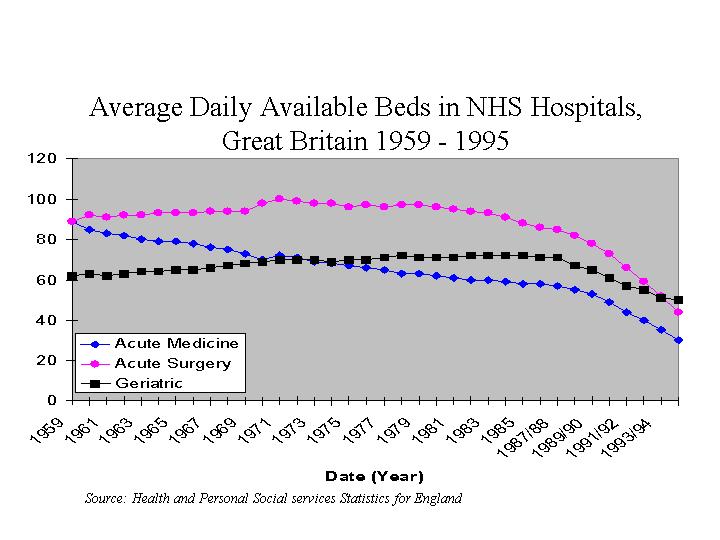

Figure 3 shows how the average daily available beds in NHS hospitals decreased between 1959 and 1995. Acute hospitals now run with near 100% bed occupancy and 'Winter' bed crises now last over 6 months of the year.

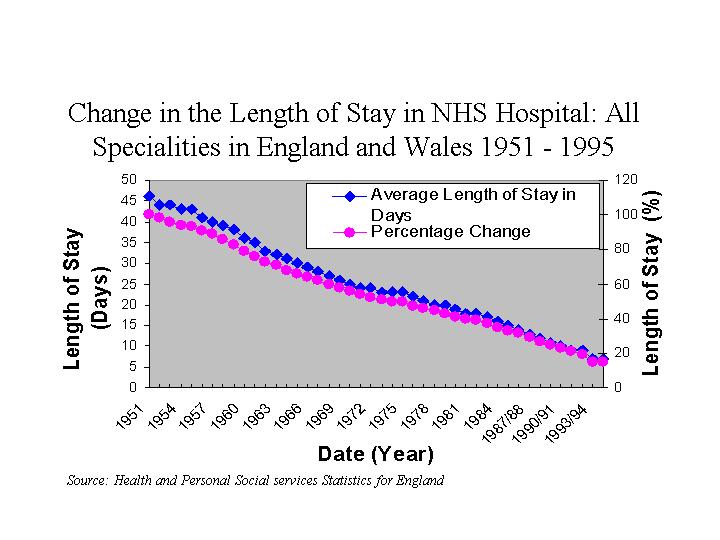

Figure 3 Change in length of stay in NHS hospitals: All specialties in England and Wales 1959-1995

There is increasing emphasis on decreasing patients' length of stay. Tactics include early discharge schemes involving intermediate care, discharge co-ordinators, bed managers and nurse-led discharge teams, and discharge to community hospitals, residential and nursing homes with 'rehabilitation' beds. Hospital resources are spent trying to meet government targets, including 4-hour waiting times, reducing delayed discharges, waiting list initiatives and 2-week cancer referral times. Severe restrictions on staffing levels and recruitment are placed throughout the trusts in order to break even financially.

Special needs of vulnerable older people

Frail older people who are ill have characteristics that are different from younger general medical patients. Immobility, instability, incontinence and intellectual impairment are the Giants of Geriatrics[1]; multiple causation, chronic course, deprivation of independence and no simple cure are common characteristics. There is immense heterogeneity and complexity; many medical conditions, each running a chronic cause, create dependence. So many older people take longer to recover following an acute illness than younger persons.

The bio-psycho-social model - square pegs in round holes.

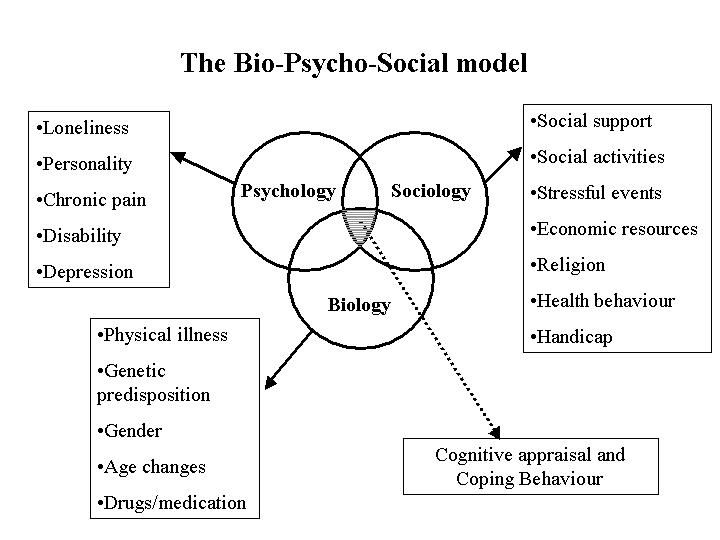

The bio-psycho-social model in Figure 4 shows how a person's independence and coping behaviour is dependent on many interacting psychological, social and biological factors.

Figure 4. The bio-psycho-social model shows how a person’s independence and coping behaviour depends on many interacting factors.

An elderly 'bed-blocker' or 'delayed discharge' may well be medically 'stable' for discharge, but will have at least one medical condition that impacts on his/her psychological and social factors to the extent that he/she is not safe to be discharged from hospital immediately. At present, acute hospitals aim for an average length of stay of about 6 days per patient, regardless of age or medical conditions. The elderly 'bed-blocker' is unable to meet this target due to bio-psycho-social factors. He/she becomes a 'square peg in a round hole'.

The Way Forward

Traditionally, Geriatric medicine filled the central role, however, within the NHS it is increasingly unable to do so because:

a. Integration into acute care (with its benefits of equal access to acute medical services for the elderly)

b. Shorter lengths of stay and shorter periods of rehabilitation, and

c. Loss of control by the NHS Hospitals of the care of the chronic sick.

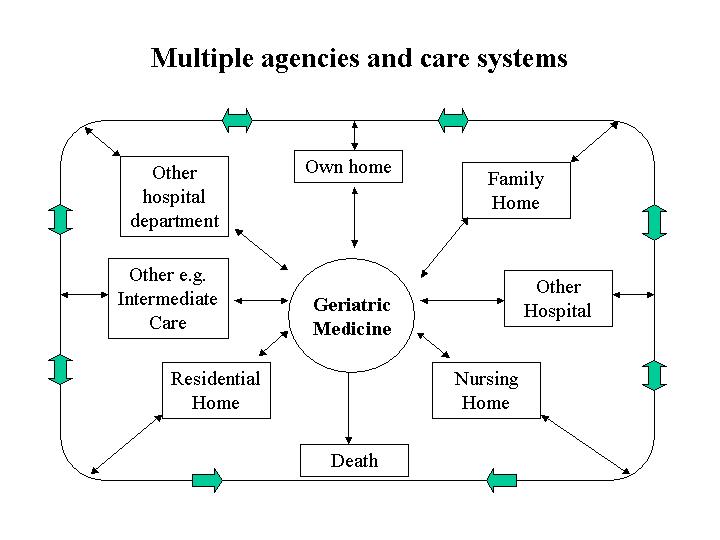

Figure 6 illustrates the interactions between different care systems and death.

Now it is unclear which department or agency is better suited to the central role. Perhaps community matrons, as proposed by the present government, will lead the way in chronic disease management in the community. Alternatively, perhaps a new, hospital based, consultant led service 'xyz'[2] or 'gerocomy'[3] should emerge like a phoenix from the ashes of the past.

1. Isaacs, B., Some characteristics of geriatric patients. Scottish Medical Journal, 1969, 14: p. 243.

2. Cang, S., An alternative to hospital. Lancet, 1977. i: p. 742-743.

3. Millard, P.H., A case for the development of departments of gerocomy in all district general hospitals. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 1991. 84: p. 731-733.

Some navigational notes:

A highlighted number may bring up a footnote or a reference. A highlighted word hotlinks to another document (chapter, appendix, table of contents, whatever). In general, if you click on the 'Back' button it will bring to to the point of departure in the document from which you came.Copyright (c)Roy Johnston, Peter Millard, 2005, for e-version; content is author's copyright,