Nosokinetics

Can Patient Choice Degrade Health Systems?

Steve Gallivan

1. Introduction

The United Kingdom is currently introducing health policy to promote patient choice. At first sight it seems morally self evident that it is a good thing to offer choice to patients concerning their treatment, so much so, that it hardly seems worth questioning. However, is this the case?There are certainly examples of system behaviour in fields other than health care where it is counter-productive to offer system users the right to choose. One such example goes by the name of Braess's Paradox1 which was discovered in relation to road traffic systems. Here a simple example is constructed showing that, in principle, such behaviour could also occur in relation to health care systems. Whether such odd systems behaviour occurs in real life, is hard to assess, although possibly this is because no one has yet thought to investigate the issue. Even so, it is useful to be alert to the fact that offering choice to patients may not always be a useful goal.

2. A simple illustrative example

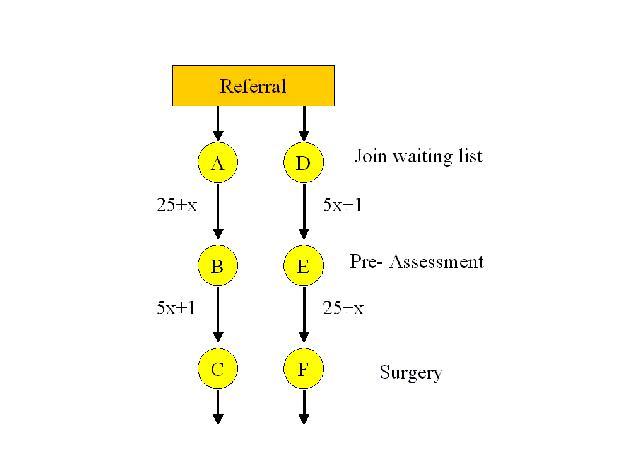

Following the ideas of Braess, consider a simplistic representation of the operation of a health care system depending whether or not patient choice is allowed. This is shown schematically in the Figure 1. Here we assume that a homogeneous group of patients are treated surgically in one of two different hospitals.It is assumed that three patients per week are referred to each hospital. The hospitals have adopted different ways of managing their waiting lists for initial surgical assessment and for subsequent surgery, although for the same throughput, both have the same overall 'processing time'. The waiting times in each part of the care pathway are assumed to depend upon the number of patients treated per week (denoted by x in Figure 1). In general, mathematical formulae for waiting times are complex, but here simple linear formulae will be used for illustration purposes (the complexity of individual formulae does not affect the nature of the example). These formulae are shown alongside the links of Figure 1.

Figure 1. Pathways through a hypothetical health care process with or without patient choice options. Formulae indicate delays for each link dependent on flow of patients x.

Without patient choice, since three patients per week are referred to each hospital, the overall 'processing time' for the two hospitals are identical for each patient (44 time units).

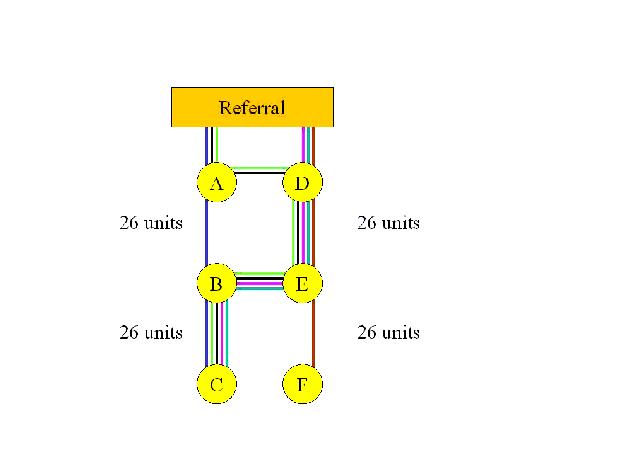

With patient choice, two options are permitted. Patients are allowed to decide which of the hospitals they will attend for surgical assessment. Also, following assessment, they may switch to a different hospital for surgery. If all patients make choices that minimise their own overall processing time, then there will be an equilibrium only if the routes chosen through the care pathway network are all individually better that any alternative that is available. Figure 2 shows the configuration of flows for which such an equilibrium is achieved. With this, all patients have the same total processing time, 52 units. It can easily be verified that any patient who wishes to deviate from this, would suffer a longer overall delay.

Figure 2. The equilibrium configuration whereby no patient can switch to a different option without incurring greater delay. Different colours correspond to different patients' routes through the health care process.

Thus paradoxically, the overall effect of introducing patient choice is to increase delays for all patients using the system from 44 units to 52 units.

3. Discussion

To understand what gives rise to this paradoxical systems behaviour, it is useful to consider health systems operation in terms of the mathematics of optimisation. Minimum total system delay occurs if patients are optimally assigned to routes through the health care process. This is the so-called 'system optimum' which, for the example given, corresponds to no patients switching hospitals.Promoting patient choice results in the emergence of a different and rather complex optimisation problem. Rather than a single optimisation problem, assignments arise from group behaviour of numerous individuals, each concerned with optimising things from their own perspective. The resulting patient assignment, referred to as a 'user optimum', corresponds to the assignments shown in Figure 2. This gives a stark demonstration of how the user optimum can differ markedly from the system optimum not only degrading overall system performance, but in this case also dis-benefiting all patients.

While this example is clearly a disturbing possibility, the optimist might trust to luck that such pathological behaviour is unlikely to occur in practice. That may or may not be the case, and at present there is little evidence upon which to base such a view one way or the other. However, what is apparent is that there is likely to be a substantial difference between the system optimum assignment of patients to routes through the health care process and the user optimum. Whether this is likely to give rise to major or minor effects in overall system performance is not known, although the author would conjecture the former. Certainly it would seem sensible to monitor and model the overall systems effects of new schemes

The consequences of Braess's Paradox are taken very seriously in transport planning, indeed the whole topic of driver route choice has been subject to a considerable amount of study. Patient choice in health care is a more recent phenomenon and there has been little opportunity to carry out either theoretical or empirical studies related to system stability properties. The example presented in this discussion highlights potentially disruptive and hitherto unforeseen consequences of introducing patient choice. This suggests that if patient choice is to be introduced there will be a need for a major programme of research to investigate the theoretical and practical consequences.

4. References [1] Braess, D. 'gber ein Paradoxon aus der Verkehrplannung.', Unternehmenforschung, 12, pp258-263, (1969)

Some navigational notes:

A highlighted number may bring up a footnote or a reference. A highlighted word hotlinks to another document (chapter, appendix, table of contents, whatever). In general, if you click on the 'Back' button it will bring to to the point of departure in the document from which you came.Copyright (c)Roy Johnston, Peter Millard, 2005, for e-version; content is author's copyright,