Century of Endeavour

Chapter 3: The period 1921-1930

(c) Roy Johnston 2002

(comments to rjtechne@iol.ie)

Introduction

In the 1920s JJ was active in trying to support the declining co-operative movement (which had been split under Partition); he did extern lecturing, initially when the war of independence was on in Dublin in TCD to trade unionists, often with Tom Johnson the Labour Party leader presiding, then later outside Dublin; these were mostly under the auspices of the Barrington Trust(1).As regards political(2) activity, there is a suggestion that JJ had been involved in support of the Thomas Davis Society (TDS), which from about 1919 and in the early 20s was a Sinn Fein 'front' in TCD. He certainly was friendly with Dermot MacManus, who was a prime mover in the TDS, and who subsequently became a military leader in the Free State Army during the Civil War, acting mostly in the West. He wrote a series of articles for the Manchester Guardian in 1923, surveying the post civil war situation, and commenting on the motivations of the people concerned.

JJ participated in the first Agriculture Commission set up in 1922 by the Free State Government. This attempted to pick up the momentum of Sir Horace Plunkett's Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction. Although most of its recommendations were sound, it was not adapted to the politics of the times, which were dominated by the demand for land-division. JJ wrote an addendum on the need for training of co-operative managers.

JJ began in the late 1920s to seek election to the Senate, although without success. He had published a book(3) in 1925 which attempted to popularise the basic concepts of economic thinking, and which contained some seminal ideas which now would now be recognised as relating the 'development economics' domain, emphasising the importance of getting a good deal for the agricultural primary producers. He also introduced the idea of the importance of knowhow as a factor of production, along with land, labour and capital; this at the time was innovative.

During the 1920s and subsequently in the 1930s JJ campaigned for increased understanding of development economics in the Irish agricultural community, continuing to use as his vehicle the Barrington Lectures(4). These had been initiated a century earlier, in the aftermath of the Famine, and were in effect a sort of outreach campaign by the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society (SSISI)(5), with the aim of avoiding future famines through enlightenment. JJ joined the SSISI in 1924. In their original form the Barrington Lectures tended to dodge the key current political issues of land tenure etc. They survived in outreach form until rendered redundant by the advent of TV in the 1960s. They still nominally remain in the form of an annual SSISI Barrington Lecture on the home ground of the Society.

The Co-operative Movement

In the earlier years of the decade, when the war of independence and civil war was going on, JJ seems to have concentrated on working with Plunkett House, doing articles and reviews for Better Business; this later became The Irish Economist and then later blossomed into the Irish Statesman. He also kept up a low-key contact with the national movement(6), corresponding with Dermot MacManus, who had been the leading light in the TCD Thomas Davis Society, and by 1922 was commanding Free State forces in Limerick. MacManus later became Deputy Governor of Mountjoy Jail. In the latter context he seems to have leaked to JJ photocopies of handwritten letters from Pierrepoint the hangman, which JJ retained among his papers as curiosities. He probably found the McManus contact useful in the journalistic work he did for the Manchester Guardian in 1923.JJ continued to publish promotionally for the co-operative movement(7) in various Plunkett House publications: an assessment of the experience of the TCD co-op, a review of the work of Sydney and Beatrice Webb, articles on Money and Credit, Free Trade and Protection for Irish Industries; this was a forerunner of his book The Nemesis of Economic Nationalism published a decade later.

In 1925 JJ began to appear in the Irish Statesman, with UCD economist George O'Brien reviewing his 'Groundwork of Economics'. JJ also had an article on municipal reform, and a letter on the Universities; at about this time he was standing for election to the Seanad. There appears the first of a series of Paris letters from Simone Tery, whom we have encountered with JJ in the Albert Kahn stream; it is reasonable to suggest that JJ might have contributed to encouraging her interest in Ireland, about which she wrote articles and a political book for the French market.

It can credibly be suggested that most of JJ's writings during this time were dedicated to the development of a public profile in the context of the 1926 Seanad election, in which however he was unsuccessful.

He had earlier had a supportive role in connection with the Boundary Commission, and he remained friendly with Kevin O'Shiel, the Secretary and author of the Report, during the 1930s and 1940s; I remember several social occasions, viewed from below, as a child. He kept among his papers some cuttings relating to the Boundary Commission, from 1924, and his copy of the Report is annotated. There is also a map of the Ulster and the six counties, with the distribution of electoral majorities by parish marked in. This appears to be a draft or earlier version of the map given on p83 of Kevin O'Shiel's Handbook of the Ulster Question, as the style is similar, though the representation is different.

The Barrington Lectures

JJ's main concern in the mid to late 1920s was to propagate in the outside world a critical view of the economic factors to be taken into account in the Free State situation. His main vehicle for this was the Barrington Lecture(1) series, which he managed single-handed between 1921 and 1932, when he managed to get them back under the control of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland (SSISI), from which they had lapsed after the First World War. During the War of Independence and the Civil War he delivered the earlier 1920s Barrington lectures on TCD ground, where they attracted support from the trade unions; Tom Johnson, leader of the Labour Party, on occasions presided.Later in the decade he brought them round the country, making use of the Carnegie Library network, and later the Vocational Education Committees, when the library system was brought in under local government. In post-civil-war excursions to various remote places he seems to have had trouble in getting an audience; he mentions this retrospectively in a Seanad speech, in the 1940s. He attempted to prevent the withdrawal of the Carnegie Trust to Scotland, offering to take over the field-work after the resignation of Lennox Robinson who had been the Secretary of the Trust in Ireland, but was unsuccessful in this(4). He attempted in the correspondence to use the Barrington connection as leverage:

"The establishment of the Irish Free State has made more important than ever the task of creating a public opinion capable of appreciating the economic issues which are constantly being presented to us by our legislators. By means of its circulating libraries the Carnegie UK Trust has already done invaluable work in this, as in other, directions.

"For the last four years I have held the position of Barrington Lecturer in Economics. The Barrington Trust is a century-old Trust. The function of the Barrington Lecturer is to give lectures on Social Economics in 'the towns and villages of Ireland'. I have felt for some time that the value of these lectures was diminished because they were not preceded and followed by a course of appropriate reading on the part of those forming the audiences or classes.

"I have also felt that the efforts of the Carnegie Trust to create a reading public in rural Ireland would be assisted if the Library movement were more closely associated with an Institution like the Barrington Trust, which makes it possible for at least one Lecturer to give lectures or hold classes in out of the way places. Latterly, under the auspices of the Barrington Trust, I have been holding classes for non-university students in Dublin, but it is my intention to make a fresh start in the rural districts after the end of the present calendar year. It was also my intention to choose those districts where the Library movement had been most successful, with a view to the closer co-ordination of the work of the two Trusts."

In the course of further correspondence with Colonel JM Mitchell, the Carnegie Foundation executive in Scotland, JJ attempted to use the good offices of the Foundation to help him get access to the new County Library network, fearing perhaps that otherwise his TCD background might be a barrier. The Colonel replied positively for situations where Carnegie contacts had existed, namely in Antrim, Fermanagh, Galway, Londonderry(sic), Kilkenny, Sligo, Tipperary, Tirconaill, Wexford, Wicklow. JJ replied specifying his time-constraints, and offering 25 lectures per annum. The Colonel then back-tracked, referring the matter to the new County Committees. It seemed also that he regarded lectures in economic and social science as being subversive, especially in the then Irish context, and wanted to distance the Carnegie Trust from the process.

Later however there came a letter from the Colonel to the effect that he had heard from Miss Josephine M Walsh of Wexford, who expressed interest. He urged JJ to get in touch directly and gave the address. So the Wexford series was set up successfully; there is among JJ's papers a copy of a notice issued by the Wexford County Council, advertising a short course of Lectures in Economics, organised by the Library Service, in the Town Hall, the first one on "Some Consequences of Economic Law" being fixed for Thursday March 8 1926 at 8pm. This was also in the lead-up to the 1926 Seanad elections.

There is also among JJ's papers a page setting out the topics for what look like a series of six lectures, along lines somewhat similar to the Table of Contents of the 'Groundwork', though differing in detail. It seems he hoped to give the series cohesively in the one location, and the purpose was didactic. Later, in the 30s, the lectures tended to be more critical and controversial on current affairs, and to be one-shot local events in various places.

The 1922-24 Agriculture Commission

JJ was recruited to serve on the Agriculture Commission(8) which sat from 1922 to 1924, along with George O'Brien, JP Drew and others. In order to have been so invited he must have been in good standing with the new Free State Government. His prior work(9) lobbying the Convention, and his work in support of the Thomas Davis Society in Trinity College would not have gone un-noticed, as well as his work with the Albert Kahn Foundation, which had both a national dimension, via his Garnier briefings for influencing French public opinion, and via his earlier work in 1916 on French agricultural production.

The Commission came out with a series of interim reports, on issues considered urgent. The series covered tobacco (in which there was some pioneering interest, though it never came to much), butter, eggs, credit and 'scrub bulls'.

The final report was basically a re-iteration of the classical Department policy from the Horace Plunkett era, derived from the Recess Committee, with emphasis on education and organisation, and as such was perhaps not in tune with the times, which were politically dominated by a populist demand for land re-distribution. JJ included a signed addendum in which he advocated resourcing the training of co-op managers, and also the imposition of an export tax on live cattle. He had early identified the need for combining tillage with livestock, enabling the finishing of cattle for beef by stall-feeding in winter, and supporting expanded winter dairying. This implied a co-operative approach to large-scale managed commercial farming, and was inconsistent with the division of land into small units. The Report was, unjustly, condemned in the political media as a 'rancher's charter'.

Political Journalism

There was a series of articles in the Manchester Guardian in 1923, which are JJ's from internal evidence, and which are referenced in the Garnier correspondence. These were headed 'an Inquiry into Ireland' and I have summarised them more fully in the political stream(10).In the first article JJ tried to explain why the Government had found it so hard to restore order, interviewing Republican supporters. It is difficult to organise the townspeople in self defence; they prefer to keep quiet and stay neutral. The Government depends totally on the Army, which is inexperienced and ill-disciplined. There are plenty of trained officers around, but the government is slow to take them on; too many British ex-officers would give the Republicans a propaganda point... Republican support is young unemployed, farmers sons etc.... professional men are withholding tax, agricultural labourers aspire to own land. Farmers withholding annuities worry about law enforcement regarding arrears.

Then on April 13 1923 JJ wrote of an interview with a group of six hard-core Republicans; regarding the election, they held that there was never a majority for the Free State vs the Republic, only a majority for the FS vs war. They would not feel bound by plebiscite unless the threat of war was removed. He quoted a source: '...the materialist majority are sheep who must be driven by the minority of energetic idealists..'.

The April 14 1923 article contained a report from 'our special correspondent' on the Free State budget, which ran at an expenditure of £30M, at a deficit of £2.3M. Continuing the 'inquiry' series, JJ tried to find out what the 'republic' concept meant; most Free Staters saw the Free State as the 'stepping-stone' to the Republic. Some fear that a Republic now would mean civil war in the North. The majority would have voted for the Republic were it not for the threat of war. But now that civil war has begun, perhaps not; the 'republic' concept is now in disrepute.

The strong farmers had been the backbone of the war of independence, and it was the threat of conscription that had activated them. These however are now solidly Free Staters. 'The uncompromising republican idealists are drawn from the ranks of the intellectuals: professors, civil servants, teachers, young priests and women of leisure. These can't make successful war without the support of the farmers.'

April 17 1923: JJ described conditions in 'regular' country (there are 3 parts: regular, irregular and Ulster)..... Labourers quietly expand their half-acre to one acre by extending their fencing. Strong farmers do land deals with landlords, but can't agree on how to divide. The Land Bank refuses to help because they give priority to landless men. Law is beginning to exist, even for landlords. The unarmed Civic Guards are active.

April 18 1923: JJ spent time in Limerick, where the Free State troops were said to be 'the most effective in Ireland'; the average age of officers was 21, generals 30; there was said to be no looting or bullying. Experience of republicans was bad; there was much looting. However the Guards were becoming effective, and had established the ability to arrest without arms.

I suspect that JJ's contact with Dermot MacManus was relevant here. MacManus had written to JJ from Limerick earlier in the year, and even if demobilised would have been in a position to help with introductions and contacts.

He picked up some lore about de Valera in Tralee; a big crowd came to hear him; he asked them to vote for the Republic, and they all put their hands up. Dev went away thinking he had the people behind them and started the war. But the people had only come out of curiosity, and they felt that they would get into trouble if they didn't put up their hands. 'That was the beginning of the irregularity'.

April 19 1923: In Tralee he picked up a picture of 'irregular' mountain country. The Free State was in Cork and in Tralee and in the coastal towns. .... It was impossible for the Free State to take over, due to lack of material and inexperience. The war here could drag on for the summer.

April 21 1923: JJ tried to analyse the thinking of the 'idealists'; their concept of culture was somewhat vague: '..one man cited the co-operative movement as an example of the way the Protestant aristocracy, even at its best, has never been anything but a fallacious guide endeavouring to persuade people to substitute material ends for the spiritual ideal of independence..'. There was no clear idea how Europe should relate to tropical countries.. no idea of socialism... some talk of 'co-operative commonwealth'; '..the small-nation system will put an end to the sins of imperialism, capitalism and militarism..'.

He evaluated them individually as being humble-minded, but '...as a class their conceit is astounding....the utmost concession...to democracy is to agree to be bound by the decisions of the nation in its best moments. But they themselves are to decide which are the nation's best moments....I am sure they can't be induced to drop their opposition to the Free State... they are as ruthless as any bureaucracy or autocracy... if only they could be persuaded to marry and to have children!..'.

April 23 1923: JJ recounted some anecdotal travel episodes in Wexford, Waterford and Carlow. He stayed in a big house rented by a teacher and a Presbyterian Minister, near Kilkenny; Redmond supporters. He met a gardener who was out of work, and as a consequence somewhat blind to the patriotic virtues of burning country houses. He took a dim view of the type of pub-talk patriots who were being recruited to the Guards, and given land.

April 24 1923: there was a general desire to get back to work. It should be possible to establish a dead meat industry, and other industries subsidiary to agriculture, putting the money to work that was currently lying idle in the banks. No-one will venture money while there is danger of explosions etc. The Republican hope that the executions would bring people to their side was misplaced. Most 'irregularity' now is just criminal. A barracks was burned in Kilkenny because Guards interfered with salmon poaching.

The final article, on May 2, focused on the land question, which remained unresolved, with 25% of the land still under landlord nominal control, though with much rent arrears. He summarised the rest of the issues thus: '...the Ulster problem, the Labour problem, the demobilisation of 50,000 men, 2000 irregulars on the run, 15,000 republican prisoners, splitting the grass ranches and completing the land purchase..'.

Steps Towards 'Political Economy'

JJ joined the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society in 1924, as an Oldham recruit, and was elected to the Council in 1925(5). He remained active on the Council for some decades. His first paper to the SSISI was on 'Some Causes and Consequences of Distributive Waste', delivered March 10 1927. This was the result of some work done with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, which enabled him to travel to France to do some international comparisons. The results of his French studies are absent from his SSISI paper, but they surfaced strongly in the Prices Tribunal of 1926, to which he contributed an extended signed addendum, developing the argument for a National Economic Council to integrate the results of the various disparate enquiries and bodies which existed on economic matters. I have so far been unable to trace any actual integrated Rockefeller Foundation Report, though I have a copy of his application.In March 14 1925 appointments were finally made in TCD to the School of Commerce: JJ at last got his lectureship in economics, CE Maxwell on economic history, John Cooke on commercial geography; there were lectures in French, German, Spanish etc, and TS Broderick lectured on statistical methods. The new School of Commerce seemed to be taking shape credibly. The Commerce School Committee had Bastable as the Professor, with Duncan and JJ as his Assistants. Bastable was also the Regius Professor of Laws.

The syllabus remained basically that of the pre-1920 Diploma; it showed no sign that JJ's efforts to promote the co-operative principle in commerce, via his Barrington Lectures and via his work with the Dublin University Co-operative Society, had any success. There remained however a nod in this direction, in the form of the retention of the Recess Committee Report, which had been on the syllabus since the beginning of the Diploma in 1906.

During the mid-20s we had the ESB and the Shannon Scheme, the Purser Griffith vs McLaughlin controversy regarding energy development policy; JJ does not appear to have been directly concerned with the 'development economic' aspects of this, though he retained in his possession TA McLaughlin's seminal pamphlet on the Shannon Scheme, in which the latter drew on the experience of the electrification of Pomerania. JJ also had the ensuing Borgquist et al Government Expert Report, which he got from EH Alton who then represented the College in the Dail. Both these documents are among his papers. I remember him, in the early 30s, when living in Newtown Platin, near Drogheda, pointing out the new ESB high-tension poles with a sense of pride in achievement.

The Prices Commission: French Influence via Rockefeller

The TCD Board certainly was aware of JJ's economic work in the public service: on March 19 1926 there is a minute '...as the Government is desirous that Mr Joseph Johnston should be free to devote as much time as possible to the work of the Profiteering (sic) Tribunal and to the investigations incidental to it, and the Minister for Finance has agreed to pay deputies for him next term, he is allowed to take advantage of this arrangement next Trinity term.' Thus we have a further example of JJ's concern with, and availability for the solution of, problems of the outside world. There was a further reference on April 24 1926, in which leave of absence is confirmed for Trinity Term, with the School Committee to decide about a substitute. He was also granted a further fortnight in 1926, and one in January 1927, to take up a Rockefeller Fellowship for Economic Research in Europe.In JJ's Addendum to the Prices Commission Report he described himself as Rockefeller Fellow for Economic Research 1926-27, and this embodied the results of his recent studies in France. He put emphasis on consumption as being the generator of demand for production, and on the importance of the distribution system working cost-effectively, so as to maximise the ease of access and affordability of the goods produced. He had in mind the potential for the development of the consumer co-op movement as a more cost-effective alternative to the large number of small retail outlets. He advocated a licencing system for retailing.

He produced evidence for this from his French studies, and went on to outline how the National Economic Council concept had been realised in France. The relevant sections I quote in full:

"43. By a decree of the 10th January, 1925, a National Economic Council was established in France. The object was to create a school for the dispassionate study of economic questions, from the point of view of the general economic interest, and to supply an organ of "inter-ministerial" co-ordination. In conformity with this idea it is attached to the office of the President of the Executive Council - not to any Ministerial Department. It is there to be consulted by the Government, but it has also the right to give its advice unasked on any matters in which it chooses to interest itself. Its membership includes expert officials from the Ministries of Finance, Agriculture, Labour and Commerce.

"It may also summon non-official experts --"techniciens", economists, and jurists to assist in its deliberations. The ordinary membership is based on a semi-representative principle, the governing idea being that the consumers' point of view should predominate. The Government decides what organisations shall be represented, and each such organisation freely appoints its delegate to the Council.

"There are 47 such delegates. Three are appointed by Consumers' Co-operative Societies, and six others represent directly various aspects of economic consumption. Eleven delegates represent managerial services in industry, agriculture etc, while fourteen represent wage-paid labour of various types.

"Industrial capital is represented by three delegates, land-ownership (urban and rural), by two, while the Capital associated with banking, insurance, and the Stock Exchange has a representation of three.

"44. Reports of the National Economic Council have been published in "Annexes" to the "Journal Officiel". One such report deals with hydraulic production and distribution of electric power. Another deals with co-operation and agricultural credit as means of intensifying agricultural production, another with the electrification of the countryside, another with live stock, etc etc. It would appear from recent experience that the Saorstát has need of a rational and enlightened public opinion on questions like these, and in this connection a suitably constituted National Economic Council might play a useful part.

"45. It should contain in the first instance official experts from at least the economic Ministries -- Finance, Agriculture, Commerce and Fisheries. To these should be added experts from the Industrial Trust Company, the Tariff Commission, the Shannon Electricity Board, the Currency Commission, the Agricultural Credit Corporation, and the proposed Prices Board. The Chairman of the Currency Commission should be the Chairman of the Council, and the Secretariat of that Commission should act as the Secretariat of the Council. As in the case of France it should be attached directly to the office of the President of the Executive Council, and not to any Ministerial Department'.

"46. Delegates from the more important professional economic organisations should belong to the Council, as in the case France, and be appointed by a similar method."

JJ went on to refer back to the 1922-24 Agriculture Commission, outlining some of the problems it had identified relating to the supply of milk. He drew again on the French experience:

"55. About forty miles north of Paris, at Lyons-le-Foret, there is a co-operative creamery which the present writer lately had the privilege of visiting. It was established in 1900, as a result of the intelligent initiative of some thirty farmers, who were tired of economic dependence on private milk collecting firms. It now numbers about 400 members who are bound by contract to dispose of all their milk through it. In 1918, when the membership was 284, the Society handled 3,442,186 litres of milk. The value of buildings, pasteurising and cooling plant, milk cans, butter and cheese manufacturing plant, motor lorries, horse-drawn vehicles, etc, now runs to some thousands of pounds sterling. It was originally established, mainly by borrowed money, but its debts have since been repaid, and the position is in the highest degree liquid.

"The premises of the Society are adjacent to a railway station from which there is a convenient train service to Paris. A depot is maintained in that city, the manager of which is in direct telephonic, communication with his colleague at Lyons-le-Foret. It is also in close touch with the private retail milk vendors who are his customers in Paris. The latter are able to estimate very closely their requirements from day to day. They give their orders to the depot manager who, after a simple arithmetical operation, is able to telephone to the creamery manager forty miles away. telling him exactly the quantity,of fresh milk which he should send in the next consignment. The milk cans, which are of ten, fifteen and twenty litres capacity, are sealed at the station of departure, and on arrival at Paris are distributed direct to the retailers without necessarily being brought to the depot.

"Nevertheless, a small cheese manufacturing plant is maintained there to deal with any surplus which the retailers might not be able to dispose of. All the milk is pasteurised at Lyons-la-Foret. Any milk not required for liquid consumption is retained there and turned into butter or cheese. Thus the substantial summer surplus is kept off the fresh milk market, and at all times of the year waste is reduced to a minimum. The suppliers are paid in proportion to their total milk deliveries -- a higher price of course in winter than in summer. In order to encourage winter milk production the refund, or dividend, payable at the end of the financial year, is paid only in respect of winter milk.

"56. The Society at Lyons-la-Foret is only one among some dozens of such societies, situated at an average distance of about fifty miles from Paris. Together they contribute one-third of the total fresh milk consumed in that city. The other two thirds are in the hands of two large private firms. Some of these societies go in for the manufacture of casein in the summer. I am informed by Senator Donon, President of the Federation of the Co-operative Creameries in the Parisian region, that certain societies find the manufacture of casein so profitable that they are able to pay the same uniformly high price for milk winter and summer.

"57. Twenty years ago, before the inauguration of this movement, milk was frequently sold in the country at nine centimes a litre to be re-sold at thirty in Paris. According to Senator Donon the position in the winter of 1926-1927 was as follows:-

"Collection, pasteurising, cooling, transport to Paris and distribution in Paris cost in all forty-five centimes per litre. The retailers, were allowed a margin of gross profit of fifteen centimes. The consumer paid one franc fifty centimes, and this left ninety centimes a litre as the farmer's remuneration."

The above figures are of course subject to wartime inflation, but the argument is clear: the ratio between farmer and consumer prices has been vastly improved by co-operative organisation of the distribution system.

The Protestant Role in Free-State Politics

There is among the few books JJ retained in his retirement the proceedings of a 'Conference on Applied Christianity' held in January 1926, on the theme 'Towards a Better Ireland' (11). This was an attempt on the part of the all-Ireland Protestant community to assert their role in civil society, and to address the uphill task of making democracy work under Partition. The Roman Catholic Church however did not participate.This was addressed among others by Lionel Smith-Gordon, from the standpoint of the co-operative movement, and by the Ulster Liberal Professor RM Henry, who had participated in the group who went to Asquith after the Ballymoney Liberal rally of November 1913, in the hopes of stemming the tide of the Tory-Orange conspiracy which led to the April 1914 Larne gun-running.

The Albert Kahn Foundation and the French Connection

JJ still kept contact with the Albert Kahn Foundation in Paris, and was in ongoing correspondence with its Executive Secretary Charles Garnier(12). This was his 'international network' and it undoubtedly fuelled his progression into an Irish-based 'development economics' mode of thinking. He fed Garnier with material about Michael Collins, and promoted James Connolly; Garnier used the material to promote the Irish cause in France. Through this contact Simone Tery, whose Irlande had been published in 1923, was picked up as the Paris correspondent of the Irish Statesman.There is reference in the Garnier correspondence to visits by Cosgrave to Paris, in 1923 and again in 1926, on which occasion Garnier was appalled to see him kneel before a bishop, and was thereby motivated to intensify his correspondence with JJ, with his projected book on Ireland in mind. The correspondence had been quite intense during the war of independence and civil war period. Garnier sent to JJ some unpublished research-source material, which he hoped JJ would be able to use as the nucleus of a Dublin 'Centre de Documentation' for the AK Foundation. JJ targeted the Plunkett House Library for this, but all trace of this seems to have been lost. He clearly regarded this as a more accessible location than the TCD Library, which Garnier would have preferred.

The documentation consisted of the proceedings of the meetings of a political and social studies group which had met weekly, in the Cour de Cassation, under Albert Kahn auspices. This material was not commercially available, being reserved for 'centres de documentation' in educational and research centres. Albert Kahn would have preferred such a centre to be established in Trinity College, in a small reading-room, accessible to qualified researchers.

At the time the material arrived the Civil War had not yet begun; the burning of Plunkett's house took place some time later, and JJ was optimistic about the future of Plunkett House in the Free State environment.

TCD Politics or Public Life?

JJ was active in TCD politics(13) in favour of the development of a significant school of commerce and political economy. In this he was supported by GA Duncan, who eventually got the Chair. Academic promotions, then as now, were hindered rather than helped by outreach work in 'civil society' such as JJ was doing. He engaged in a significant amount of work for the Government, on questions relating to consumer prices, and travelled abroad, on a Rockefeller Fellowship, for the purpose of carrying out international comparisons, particularly with France, where he had the prior connections, due to the Albert Kahn episode.He published his book, 'Groundwork in Economics'(3), in which he popularised the basic ideas of economics, and attempted to relate these to the needs of the co-operative movement, which was struggling to survive in the hostile post-Partition environment, the Munster producer co-ops having being severed from the Ulster consumer co-op movement. He had used the early 1920s Barrington Lectures as a laboratory for testing the 'Groundwork' ideas against public perceptions, and for promoting the concept of local co-operative entrepreneurship.

During 1925 and 1926 JJ was active in public life, with an eye to the Seanad. There are preserved letters among his papers, dated September 24 and 28, 1925, from Louis Bennett, Secretary of the Women Workers' Union; this was an attempt, in the context of the coal dispute, with a view to mediation, '..to get three or four men such as yourself, outside the Labour Movement, but interested in the working classes of Dublin, to come together and consider if they could intervene in this dispute, and at least secure a truce between the two conflicting Unions..'.

Also, dated September 26 1925, from John Busteed in Cork there is a letter seeking to enlist JJ as a judge in an essay competition organised by the Cork Chamber of Commerce, for the most constructive proposal for income tax; also one dated October 20 1925, from Michael P Linehan, Irish National Teachers Organisation, expressing doubt about the attendance of Trade Union officials at JJ's autumn course of lectures, given that the TUC was organising its own course.

Then on November 12 1925, from PJ Tuohy, General Secretary of the Irish Fishermens's Association, there was a letter seeking JJ's participation in a public meeting on Wednesday December 2 '..to focus public attention on the very unsatisfactory position of the Irish fishing industry... to review what has been done... to organise public opinion behind the just demands... particularly on behalf of a few important ports where the need is especially acute. The main speaker would be Col Maurice Moore, who was one of the vice-Presidents; the other was Thomas O'Donnell BL. The President was Rev CP White PP, and the treasurer was Prof EP Culverwell, TCD.

JJ went to this, and took out non-fisherman supportive membership for £1; there is a membership card, and a book of rules, which promote '..the benefits of combination in the sale of their produce, and the purchase of nets and gear...'. There was a standing committee named in the Rules for 1925-6, with groupings in the Dublin, Cork, Galway, Wicklow, Kerry, Louth and Donegal areas. They had an office at 5 North Earl St, Dublin. This was a serious organisation, and the fact that people like JJ and Culverwell were welcome supporters is an indication that the momentum of 'Protestant radical co-operativism' had persisted since the Home Rule period and had survived the burning of Plunkett's house by the 'irregulars'.

The 1926 Seanad Elections

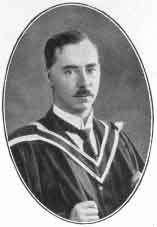

JJ made his first attempt to get elected to the Seanad in 1926; if he had succeeded he would have been in for 12 years(14). There were 3 panels: 19 outgoing Senators for re-election, 19 nominees of the Seanad and 38 nominees of the Dail. He got himself on the Dail panel, as a Government nominee. The cumbersome electoral procedure militated against the election of specialist expertise, and he failed to get in, along with others, of the calibre of Douglas Hyde.He produced a canvassing postcard with his picture, appealing '..for the support of all voters who desire the reconstruction of the Nation's economic life on sound economic principles.' He gave as his qualification his status as a Fellow of Trinity College, Dublin, and Lecturer in the School of Commerce; also Barrington Lecturer in Economics, and Member of the 1922 Agricultural Commission.

This photo of Joe Johnston appeared on his 1926 election publicity material.

The postcard continues, on the obverse side: 'In an effort to avert the serious consequences arising out of the Ulster situation, he published "Civil War in Ulster" in 1913. In "Groundwork of Economics", recently published by the Educational Company of Ireland, Talbot St, Dublin (Price 2/6), he has sought to make the elements of this important science interesting and intelligible to all Irish men and women.'

JJ kept among his papers a newspaper cutting which gave the complete panel to go before the electorate for the 1926 Seanad; this was made up of 19 outgoing Senators, 19 chosen by the Seanad, and 38 chosen by the Dail. JJ's name appeared among the latter 38; his name was followed by (G.) which suggests that he had got a Cumann na Gael nomination. There were a few (F.)s listed: John Ryan, James Dillon etc which suggests that the F stands for Farmers. Other Gs were Henry Harrison, TP McKenna, Marquis McSweeney; the G's were dominant. JJ had, it seems, joined with Cumann na Gael to get on the panel, which would be voted on as one ballot nationally.

Then finally we get the Seanad election results, analysed by constituency. JJ got a total of 1196 votes, and this compared with 1710 for Douglas Hyde, 601 for Dr McCartan, 1066 for Liam O Briain, 788 for the Marquis McSwiney, 509 for Darrell Figgis and 3722 for Sir Arthur Chance. The large numbers, leading to seats, went to people with high local profiles in certain constituencies, rather than than to people with 'specialist niche' profiles such as the ones listed, none of whom got in. Thus the Seanad electoral procedure showed itself to be flawed, its aspirant role as 'panel of experts' being frustrated by the electoral procedure.

It is interesting to identify the constituencies where JJ picked up votes. Most were of course in Dublin, but after Dublin came in order of size of vote, Laois-Offaly, Donegal, Sligo, Wexford, Carlow-Kilkenny and Cavan. This would suggest that he had gone consciously for, or at least picked up, the Protestant vote. He had subscribed to a press-cutting agency and this had picked up items in the Church of Ireland Gazette advocating that readers should vote for JJ; there had also been a review of 'Groundwork in Economics' in that same paper, linking its publication to his candidature in the Seanad election.

Internal TCD Political Barriers

Towards the end of the decade there occurred an episode in TCD internal politics which throws some light on JJ's subsequent development. The way in which the Board in 1929 attempted to set up the School of Economics and Political Science suggests a conscious move to block the aspirations of JJ, whose vision in this direction was becoming increasingly explicit, and whose public profile was expanding. On February 2 the Board asked Professor Bastable what requirements should be imposed on candidates for Fellowship in Economics and Political Science, for a competition by examination to be held in 1930. They were here reverting to the old examination procedure, and aspiring to impose a strong theoretical bias, in direct opposition to the type of experience that JJ had been acquiring, via his work on Government commissions, with Plunkett House, and with the Barrington Lectures, confirming, in the eyes of the Board, his 'enfant terrible' status.On March 16 it was recommended that the principal subject of the examination should be Economic Theory, including History of Theories, this being testable by examination. Political Science should be regarded as a subordinate subject. The Fellow so elected should be fit for the Chair in Political Economy. In other words they wanted to recruit an external replacement for Bastable, then due for retirement, other than JJ or Duncan.

In 1930 on February 12 it was noted that three candidates for Fellowship in Economics had presented themselves: JW Nisbet from Glasgow, Alfred Plummer from London (earlier he had been an Albert Kahn candidate) and GJ Walker (Oxon). Two external examiners were selected, along with Bastable; one was Pigou, a world-figure. The externs however declined to act; two other were asked, Bowley and Clapham. The exam took place in May, there were 3 papers, Principles, Currency and Economic Organisation, Governmental Functions. The examiners reports were read on June 14, after which the episode sank without trace. One can read into these events a sense of culture-shock. The world had moved on.

Family Pressures

During all this time however he was under considerable family pressures, with two grannies and three fostered nephews as well as my sister, and he had to move house several times. Of interest in the family context is a record of a visit by JJ's younger sister Ann to Budapest, at an international student Christian conference; she showed considerable insight into the post-Versailles politics of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which she reported to JJ in correspondence.(15)JJ had, as a result of his outreach and political activity, little output in the form of academic research papers. His main work was popularisation and polemic(16).

Notes and References

1. The Barrington Lectures were initiated in 1849 by John Barrington, a Dublin merchant, with a view to providing for the instruction of the Irish people in Liberal economics. Before World War 1 they had been managed by the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society (SSISI). The Centenary Volume of the Proceedings of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland, published in 1947 edited by R D Collison Black, contains background information about the Barrington Lectures. There is given a complete series of Barrington Lecturers from 1852 to 1946 in the Centenary Volume. The most notable of the Barrington Lecturers pre-war was C H Oldham, who was a Home Rule supporter and a prolific contributor of papers to the Society between 1895 and 1925. He was an early influence on JJ.2. Evidence among JJ's papers is thin on the ground, but I have collected what I can find in the 1920s political module in the hypertext. He continued to receive communications from Erskine Childers. He wrote a letter of condolence on the death of Michael Collins, which was acknowledged. There was also contact with Dermot MacManus, an ex-service mature student, who had been the prime mover of the Thomas Davis Society from 1919, and who subsequently commanded the Free State Army in the West during the Civil war. There are some intriguing hints, like copies of letters from Pierrepoint the hangman to the Governor of Mountjoy regarding clients in that institution: MacManus became Deputy Governor of Mountjoy Prison. JJ was also in the early 1920s involved in the work of the Boundary Commission, from the economic angle. There were papers to do with this, but they have vanished. I suspect them of being used by Kevin O'Sheil's biographer, and I remain in hopes of tracking then down. There is among his papers a copy of the 1923 Handbook of the Ulster Question, edited by Kevin O'Shiel, Director of the North-Eastern Boundary Bureau, which is annotated in JJ's handwriting. The missing papers, if I can find them, and which I recollect from my earlier encounter with his papers in 1971, will indicate the extent of his role in the production of this Boundary Commission report. He remained in close touch with Kevin O'Shiel during the 30s and 40s, to the best of my recollection.

3. The earlier Barrington series seems eventually to have blossomed into JJ's Groundwork of Economics published by the Educational Co in 1925, or perhaps in 1926. (There is no date of publication given on the book itself.) It was certainly being reviewed in 1926, prior to the Seanad elections. JJ seems to have had in mind that his later Barrington series, outside Dublin, would have been promotional for his book. Subsequently in a Seanad speech, he referred to the difficulty in filling a hall during this period, in this context.

4. The Barrington Lectures had lapsed during the war, and post-war the Barrington Trust had fallen out with the SSISI. JJ did a deal with the Barrington Trust and managed post-war to resurrect them, but was restricted to Dublin by Civil War conditions. His attempt to integrate them with the Carnegie library system, and take the lectures round the country on Carnegie locations, was creditable but only partially successful. He must have had in mind the development of the market for his Groundwork in Economics, into which he integrated most of his Barrington lecture material.

5. For the background to the SSISI see Appendix 6, and for JJ's first paper, Some Causes and Consequences of Distributive Waste, see J SSISI vol XIV p353, 1926-7. For the Rockefeller Foundation background in context see Appendix 5 where I overview the 'academic research and publication' thread. The French component of his Rockefeller project are absent from his SSISI paper, but they surfaced strongly in JJ's work for the 1926 Prices Tribunal.

6. Evidence among JJ's papers in third decade remains thin on the ground, but I have collected what I can find in the 1920s political module in the hypertext. This touches on JJ's work with the Boundary Commission, with Ned Stevens and Kevin O'Shiel. He continued to receive communications from Erskine Childers. He wrote a letter of condolence on the death of Michael Collins, which was acknowledged.

7. In February 1921 in Better Business we have an assessment of the experience of the TCD co-op, and then in the February 1922 issue was a review of The Consumers' Co-operative Movement by Sydney and Beatrice Webb (London, Longmans, 1921). In August 1922 there was a review of Money and Credit by CJ Melrose (London, Collins, 1920), with an introduction by Prof Irving Fisher. Better Business blossomed briefly into The Irish Economist. Then, in what proved to be the final issue of The Irish Economist in January 1923, JJ had a paper Free Trade or Protection for Irish Industries? which was a forerunner of his book The Nemesis of Economic Nationalism of a decade later. There is a gap in the Plunkett House series then until 1925 when JJ began to appear in the Irish Statesman. In Vol IV (14/03/25 - 15/09/25) we find the first appearance of JJ in this publication: George O'Brien reviewed his Groundwork of Economics. Vol V (12/09/25 - 6/03/26) contains a review by JJ of Foster and Catchings Profits and in this he referred to his earlier review of Money; this turns out to have been signed 'MS'; JJ was inclined to use pseudonyms when he wrote quasi-politically or polemically. Vol VI (13/03/26 - 4/09/26) contains a further article by JJ on Protection, presumably an update of his earlier one in the Irish Economist mentioned above. I have collected most of the texts of these papers from the Plunkett House Library, and they are available in the 1920s Plunkett House module in the hypertext.

8. The 1922-24 Agricultural Commission was set up by Minister Hogan, and was an attempt to pick up the continuity of the Horace Plunkett Department of Agriculture, and support the development of an export-oriented commercial agricultural system.

9. JJ's work in the national interest in the period between 1916 and 1922 is ill-documented, but there is in his papers correspondence with Erskine Childers in the context of the Convention, and with Dermot MacManus, an ex-service mature student, who was the prime mover of the Thomas Davis Society, and who subsequently commanded the Free State Army in the West during the Civil war.

10. For this series the Manchester Guardian introduced an un-named 'special correspondent' who had done a similar analysis the previous year on India; this would have been spin-off from JJ's Albert Kahn Report, which was not published until after the war. I have outlined the series in the 1920s module of the 'political' thread, which is overviewed in Appendix 10. There is also evidence in this material that JJ was helpful during the Civil war period in getting journalists from Britain passes from the Free State Government.

11. I report on the 'Towards a Better Ireland' conference in the hypertext, and also summarise it in the 1920s political module, where I also give some insights into JJ's religious evolution away from Presbyterianism towards Unitarianism, under the influence of Saville Hicks. Also in this module is a record of correspondence with Kevin O'Higgins relating to the Commonwealth Conference in May 1927, shortly before his assassination, and a subsequent acknowledgement of a letter of condolence.

12. We have already met the Albert Kahn Foundation, a 'Liberal International' network, based in Paris. JJ remained in correspondence with its Executive Secretary Charles Garnier right up to the 1940s.

13. In College JJ was active attempting to pressure the Board via meetings of the Junior Fellows. He was bypassed in the first School of Commerce appointments, and did not get involved until the second round. When it came to the question of developing a School of Economics and Political Science, with a Chair, the Board attempted to backtrack and to re-institute the obsolete 'by examination' procedure, though in this they were unsuccessful, with extern examiners declining to act. The specification was strongly theoretical. I have treated these issues in some detail in the 1920s module of the TCD Politics hypertext stream, as overviewed in Appendix 2.

14. He kept a scrapbook and I have abstracted this in the 20s module of JJ's 'public service and Seanad' thread, which is overviewed in Appendix 8.

15. I have given some additional background to these pressures in the 20s module of the 'Family' thread, which I have overviewed in Appendix 1.

16. JJ did claim his 'Groundwork' subsequently in his CV as presented at the time of his Royal Irish Academy election in 1943. There was substance in his claim, in that in Chapter 3 on the The Four Factors of Production he adds 'Enterprise' as having equal importance with 'Land, Labour and Capital', the conventional three 'factors of production'; he also assigns a special additional role to Government. These two concepts I think were probably innovative in the context of the economic writings of the 1920s. His nearest approximation to a conventionally 'academic' output in the 20s was via the SSISI, where the papers were, and indeed still are, peer-reviewed. I review his 20s papers in the 20s module of the 'Academic Output' stream of the hypertext, which I overview in Appendix 5, where it will be seen that his output did expand substantially in the 30s and 40s, though it still remained primarily outward-oriented.

Some navigational notes:

A highlighted number brings up a footnote or a reference. A highlighted word hotlinks to another document (chapter, appendix, table of contents, whatever). In general, if you click on the 'Back' button it will bring to to the point of departure in the document from which you came.Copyright Dr Roy Johnston 1999